1. The population of the village

It is difficult to make accurate estimates of the number of people living in the village at different times in its history. Sometimes the figures, or lists of names, refer to the townships of Great and Little Crakehall, sometimes to the Manor of Crakehall, and sometimes to an ill-defined region known as Crakehall or Crakehalls. Moreover, until the time of the first full national census in 1841, only heads of households are named in most documents and we can only guess at the size of families at that time.The Domesday survey of 1084 described two manors which together housed 14 families. Presumably this covered the areas of Great and Little Crakehall and Rand, which together therefore had a population of, perhaps, 70 people. The next account of the villages that gives a clue to population is Robert Tatershall's Inquisition Post Mortem, made on his death in 1298. This shows in the manor of Great Crakehall 18 "villein" farmers and 12 cottagers, as well as a miller and a fuller. This would only include those who owed some feudal service to the manor, however, and is unlikely to record all the inhabitants of the villages, especially of Little Crakehall. Great Crakehall must have had at least 30 families by that time. In 1301 and 1327 national taxes (“lay subsidies”) were levied on the personal goods of all the population, township by township. The lists of taxpayers are notoriously inaccurate, as many people evaded payment, and probably only the more prosperous inhabitants are recorded. Therefore the 20 families in Great Crakehall and 7 families in Little Crakehall who paid the tax in 1301 are probably considerable underestimates and it is difficult to know how they relate to the numbers given in the Inquisition three years earlier. The 1327 tax list is very short and gives no useful information. In 1450 24 tenant farmers appeared at the Crakehall manor court, but whether they lived in Great or Little Crakehall we do not know. Perhaps a reasonable estimate would be that by this time the population of Great Crakehall was about 150 people, with another 50 in Little Crakehall. This increase had taken place despite the punitive activities of the Norman army in 1168-70, very bad climatic conditions of the time that led to repeated crop failures, widespread malnourishment, and several epidemics of "plague". The first half of the 14th century was a particularly hard time for these reasons and records from all over the North Riding show land out of cultivation, farms unlet, and the population unable to pay their taxes. In Crakehall in 1334 the inhabitants were only able to pay about one third of the tax they had raised in 1301, and this was reflected in all the neighbouring villages. Cowling may have become permanently shrunk at this time, never regaining the 14 families it had had in 1301. Epidemics of the plague swept through Richmondshire again in 1421, 1433 and 1438. In 1440 the farmers in Richmond could not pay their customary fee farm rent to the lord because "very many ......inhabitants of the said borough have been swept away by the plague and other diseases.......so that they abandoned their houses to desolation , wandering as mendicants about the country with their wives and children". Despite these trials and tribulations, the population and its prosperity continued to increased. Surveys of 1554, 1602 and 1630 list in Great Crakehall 30 houses and cottages and a mill belonging to the Lordship of Middleham, and another 12 houses and cottages and a forge belonging to Coverham Abbey - a total of at least 42 dwellings, with perhaps 180 inhabitants, excluding any freeholders, who would have been excluded from the surveys. National population statistics for this period suggest that the population of a parish can be estimated from the average number of births recorded in the Parish Registers. On this basis the figures from Great Crakehall from 1580-1589 give a population of 159, and 90 for Little Crakehall, in reasonable agreement with the manorial surveys. In 1674 the Hearth Tax returns record 44 houses in Great Crakehall and 22 in Little Crakehall, much as in 1554. The number of people called to the manor court in the same year was 65, which would have included the tenants of at least 4 farms and cottages in Little Crakehall that were part of the manor. If all these were heads of households we would have a population of about 240 for Great Crakehall, including farm labourers and servants "living in" . It is impossible to arrive at a better estimate from the evidence available.

A later estimate of the population of Great Crakehall can be made from the records of the manor courts held by Miss Turner in the middle of the eighteenth century (read them HERE). In 1733 all the tenants and freeholders of the manor of Crakehall (mostly inhabitants of Great Crakehall) were summoned by name to the manor court. 75 people are listed, presumably the heads of all households in the village. On this basis the population of the village must have been around 300. Miss Turner's Steward, Mr. Bunting, clearly made an effort to ensure that the roll call of the manor was accurate, because the list for 1736 has annotations to several names indicating that out of a draft list of 81 persons 2 had died and 6 had removed from the village. In 1801, and the first national census, the combined populations of Great and Little Crakehall amounted to 460 people, probably not many more than in 1733, but there was a rapid rise over the next 50 years, reaching a maximum of 590 in 1851. A lot of this increase seems to have been due to growth of Little Crakehall. In the 16th and 17th centuries Little Crakehall consistently had about half the population of Great Crakehall. However, the 1871 census shows a total population in the two villages of 555, with 297 in Great Crakehall and only slightly fewer people, 258, living in Little Crakehall.

Vague though they are, these figures seem to show that the main growth of Great Crakehall happened in the 17th century. After that, the planned layout of houses around the green and the early establishment of farmhouses out in the fields may have restricted opportunities for new house building. Indeed, a stroll round the village confirms how little new building took place there between the 18th century and the 1950s, though a lot of the houses were rebuilt, on the same plots, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In Little Crakehall, however, scattered development continued to take place on the freehold land throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as the population grew.

English Heritage's Images of England website gives brief descriptions and dating, and some photographs, of all the listed buildings in Crakehall, mostly dating from the 18th century.

From about 1860 the population of rural England declined sharply, and Crakehall was no exception to this general trend. The agricultural depression and farm mechanisation reduced employment for agricultural labourers and families began to migrate to the growing industrial centres of Teeside and the West Riding in search of work. Between 1851 and 1901 the population of the two Crakehalls fell by nearly 40%. The 1871 census shows 21 houses in the two villages unoccupied - some of them, no doubt, vacated by families that had left the village. Since then the population recorded by the census has fluctuated between 360 and 390 until the 1970s, when new houses have began to appear in the villages. In 1971 the population of the two villages together was 370, and between then and 1985 planning permission for a further 42 houses was granted. Two things have fuelled the recent expansion - wide car ownership and a willingness to travel ever increasing distances from home to work has stimulated both the modernisation of old property and the building of new family housing. There has been a similar demand from retired people, both those from the area seeking smaller, more manageable bungalows and 'incomers' simply wanting a more relaxed village atmosphere after spending their working lives in the cities. By 1985, there were 90 houses in Great Crakehall and 94 in Little Crakehall. About 80% of the householders in both villages owned at least one car and nearly 40% of the houses were occupied by retired people. Since then further houses have been built in Little Crakehall around Coronation Road. It is remarkable how almost all this modern expansion has taken place in Little Crakehall. The 1871 census shows that there were 93 houses in Great Crakehall, of which only 79 were occupied. In Little Crakehall there were 69, of which 62 were occupied. The number of households in Great Crakehall has thus hardly increased at all in the last hundred years, while the increase in Little Crakehall seems to be considerably less than the number of new houses built there! What these confusing figures disguise is the extent to which tiny cottages were amalgamated into larger, modernised houses during the 20th century, particularly after World War II, the considerable number which have been demolished, and the much smaller households.

2. The pattern of society in the village

The peopleThe slow change of population until modern times hides dramatic alterations in the types of employment and social status enjoyed by the village people. The feudal status of the population in the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries had been replaced, by the middle of the 16th century, by a population of prosperous farmers who held their farms almost inalienably, by copyhold, and who called themselves yeomen. Their families had prospered by taking advantage of two important changes in the villages. In the 14th century the lord of the manor abandoned forever farming his demesne land himself, and instead let it out to his tenants at regular rents. The farmers no longer had to work the lord's farm as well as their own and many of them were able to enlarge their farms into units big enough to yield surplus produce that could be sold for profit. The more prosperous of them expanded even further, by leasing farms from Coverham Abbey and, presumably, sub-letting the houses, or even the whole farms, at a profit. The sale by the lord of Hornby of the freeholds of the farms in Little Crakehall to the tenants, and similar smaller scale sales in Great Crakehall following the sale of the manor by the crown, created a new group of freeholders by the early seventeenth century. Ownership of land brought with it several important rights and duties, including acting as juryman at the Quarter Sessions courts that carried out most of the County administration. "Yeomen" from Little Crakehall appear on the jurors' panels from the earliest Quarter Sessions records of 1607, when a juror was required to be a freeholder with land worth at least £4 a year. Mitchells, Clarkes and Lucas's served regularly throughout the century. By 1619 Richard Mitchell and Henry Lucas were called "gentlemen" and both of them served a term as High Constable for the Hang East wapentake, as did Lucas's son John, after him. Over the same period other Crakehall yeomen begin to appear as jurors - John Clarke, John Tailor, Francis Harrison and John Lucas from Little Crakehall and Robert Collinson, William Jackson and Miles Metcalfe from Great Crakehall. Miles Metcalfe is also described as a gentleman by 1628. Between 1607 and 1650 15 different Crakehall men appeared on the jury, while between 1650 and the turn of the century an additional 18 served, many of them from Great Crakehall.

As well as these yeoman and gentleman farmers, whom we can recognise from the rentals and surveys of the village, there were skilled craftsmen and tradesmen. The miller, the smith, the wheelwright, were esssential members of the working village, as were the largely unrecorded farm labourers and servants. There were also several local industries, which will be described in a later chapter. The social status and prosperity of the miller are shown by the will and inventory of Richard Vittie, the miller at High Mill who died in 1621. His goods were valued at over £30, a very large sum of money for the time. For comparison a weaver in Great Crakehall, William Ward, had goods, including his stock and equipment, worth £7 in 1608. The miller was able to leave annuities for the poor of both Bedale and Masham, and his best clothes including "my capp and my sparke of velvett brittches", worth £2-10s, to his two brothers, as well as "the last p't of his aparell geven to a poor boy , [worth] 2 shillings" - a worsted doublet. The household goods included a feather bed, table napkins, two swords, two chairs with cushions, five pewter candlesticks, a chamberpot, a chafing dish and a "brasse vessell". All these items are almost unique amongst the residents of Crakehall so early in the 17th century. Vittie must have lived in considerable style. He had, however, blotted his copybook: he wrote in his will, "Item, whereas Als [sic] Mason dothe father a childe upon me....... I do give unto [her] towards the bringing up of the said chiled 40 shillings ". Perhaps his charitable legacies were in recompense for this.

By the nineteenth century labouring on the land and domestic service had become principle sources of employment in the village. These people are almost invisible in older documents, but Victorian local government and the national census provide much more written evidence. In 1851 (see the Census details here)35 people in Great Crakehall were working as indoor domestic servants, with another 5 in Little Crakehall. The 1871 census enumerators' returns (see them here) show that this had apparently decreased to 22 people in Great Crakehall and 5 in Little Crakehall. However, this was partly due to the absence of the family from the Hall. In 1851 the Pulleines at the Hall employed 10 indoor servants - butler, housekeeper, footman, cook, nurse, lady's maid, 2 housemaids, a kitchenmaid, and a dairymaid, as well as a gardener and a groom who lived on the premises. The gamekeeper and the coachman lived elsewhere in the village. In 1871 only the cook, ladies maid, one housemaid, the laundry maid and the kitchen maid were there. Miss Robson at Crakehall House had a cook, housemaid and general servant and the vicar had a housekeeper, housemaid and groom. Several of the prosperous tradesmen, such as the landlord of the Bay Horse, Mr Eden the grocer and William Hall the schoolmaster also had one or more general servants. Others worked as general indoor servants on the big farms. In 1871 five households in Little Crakehall, including Mr Sherwood at Kirkbridge and John Boddy at the mill, each had a single domestic servant. Even more people were employed in outside work of the farms, describing themselves as agricultural or farm labourers.

Some population statistics from the censuses of 1851 and 1871 are compared below:

| Great Crakehall | Little Crakehall | |||

| Year | 1851 | 1871 | 1851 | 1871 |

| Total Population | 330 | 298 | 264 | 258 |

| Children and “Scholars” | 105 | 85 | 86 | 113 |

| People older than 65 | 28 | 23 | 18 | 23 |

| Housewives under 65 | 47 | 47 | 37 | 35 |

| Domestic servants | 37 | 28 | 5 | 5 |

| Farm labourers | 31 | 29 | 33 | 24 |

If we exclude children and scholars, women who are identified as housewives and people over 65 years old we arrive at working populations of 150 and 123 for Great and Little Crakehall in 1851 and 143 and 87 in 1871. Almost a half of these were labourers or domestic servants.

The poor

The census occasionally records a "pauper" in a large household - presumably an unemployed dependent relative. In Little Crakehall there was a "paupers cottage" , behind Mastiles farm, that had been provided by the "Lucas Charity" in the seventeenth century and was still in use in 1871. It appears to have been built by John Lucas acting as a trustee of the land left to the poor of Little Crakehall by William Clarke in 1650 (see the details). In 1673 the Justices of the Peace at the Quarter Sessions had ordered:

For as much as this Court is informed there is no churchwarden or overseer of the poor in Little Crakehall - it is ordered that the inhabitants do forthwith provide a convenient habitation for a poor man who has several times complained to this Court for remedy

This was probably the reason the cottage was built. Part of the land left by William Clarke was let separately by Lucas at an annual rent of 8 shillings, to provide an income for the charity. It was originally administered by the parish, later by the poor law overseers, and eventually by the parish council. Between 1903 and 1906 the Parish Council spent a lot of time discussing what to do with the old cottages. By then they were derelict and the garden was being used as an allotment by Luke Sedgwick. Eventually the council paid him £4 to quit his tenancy, and the cottages were demolished.

From 1834 the new Poor Law set up local Parish Unions, with workhouses and a formal system of poor rates and financial support. You can read about the Bedale Union and Workhouse on Peter Higginbotham's excellent website HERE.

A few of the papers of the Overseers of the Poor for Crakehall survive in the Clifton Castle papers. They are mainly concerned with determining whether applicants for poor relief were eligible through a genuine connection with the village. If an applicant was rejected, the overseers issued a "removal order" that disclaimed responsibility and forced the poor person to seek support elsewhere. Their records convey a vivid impression of the tribulations faced by poor people in rural areas. In 1841, the York overseers tried to remove a poor man, William Carter, to Crakehall, but Crakehall disputed his right to support in Crakehall, on the grounds that he had never occupied property in the village worth £10 a year for 40 successive days. Mr Carter's history shows that he came originally from Aiskew, where he lived for 40 years with his father at Ruffles Corner. He married in 1798, and in 1805 he rented a house in Aiskew for £18 p.a., where he lived for the next four years while working on Mr Foss's farm. By 1810 he had saved enough to move to a smallholding on the edge of Nomans Moor in Crakehall, rented from William Castling for £4 p.a. Over the next few years he gradualy acquired more land - he enclosed two small fields from the common, rented a field there from Mr Dodsworth, and another from William Wood of Pond House in Cowling. His total rent by this time was £9 -10 -0, but he estimated that the field enclosed from the common, for which he did not pay rent, was worth another 10 shillings a year. At times he and his wife had not been able to support themselves from this tiny farm; in the 1820s, in particular, they had received poor relief from Aiskew. They retired to York in 1835, but by 1840 they were in financial difficulties again. The Crakehall overseers were adamant that Aiskew had shown their responsibility by paying Carter relief before, and they refused his application. What happened to the poor couple we do not know.

Servants and labourers who were too ill to work were in a terrible position if they had no relatives to support them. Even if they had a strong case for settlement in the village, the overseers seem to have used every delaying tactic they could find. Mary Stelling of Croft became "third servant" to William Moses of Crakehall in 1827, at the age of 17, but lost her job after a year when he was bankrupted. She later worked for John Pease of Hutton Hang, but she began to suffer from inflamation of the eyes and was paid two shillings a week by the overseers of the poor in Crakehall while she was unable to work. In 1846 she became very ill and was too poorly to leave Hutton Hang. The Leyburn poor union temporarily looked after her and applied to Crakehall to support her when she was well enough to move. Not only did John Cannon, the Crakehall overseer, refuse for months to accept her, despite a clear duty to do so, but he then refused to pay Leyburn's costs when he could delay no longer. Eventually Leyburn obtained a court order against Cannon to force him to pay.

Poor widows could also find themselves with no means of support. In 1847 the Crakehall overseers considered the case of Ann Hall, aged 60. She was the widow of a sergeant in the North Yorkshire Militia whose father had come from Crakehall. She had not had an easy life - the couple had had seventeen children, of whom only six survived, and after the disbanding of the Militia they had lived in poverty in a rented room in Richmond, which they only obtained because of her husband's connection with the military. After his death Ann and her children were evicted. Ann and her eldest daughter scraped a living for the family by looking after the poultry at Hornby Castle, and later Ann worked in the kitchen there, for which she was provided with an estate cottage. When she became too infirm to work she was taken in temporarily by her son in law in Richmond. He could not afford to support her, and after much arguing the Crakehall overseers agreed to give her help.

Orphans, too, often became the reponsibility of the overseers, whose policy was to arrange apprenticeships for them as soon as they were old enough (over 13 years old). They seem to have done their best for the children. A "Register of Parish Apprentices" records five cases in Crakehall between 1806 and 1821. The first of these concerned Thomas Calvert, aged 13, who was "bound" to George Brown, a linen weaver in Hornby, until the age of 21. Six years later his younger sister was sent to work on William Outhwaite's farm, also in Hornby. Another boy was apprenticed to a linen weaver in Burton Leonard, while two others went to local tailors.

The money available to the overseers came from a local poor rate. This was 4 pence in the pound in 1840, yielding an income of £49-15-5d. The agricultural depression of the 1840s put an increasing burden on the parish, however, and by 1845 the rate had been increased to 24 pence in the pound, yielding £299-4-8d. This was necessary to support the increasing number of destitute people in the village. In 1845 an average of ten people from Crakehall were in the workhouse in Bedale, while another fifteen were receiving "out relief". By the end of 1846, the number of people receiving out- relief had risen to 29, and although far fewer were in the workhouse the total number of people needing help only started to fall slightly at the end of 1847. The overseers calculated that it cost about 6 pence a day to support one poor person - payments were generally between 2 shillings and 3 shillings and sixpence a week, though a widow with four dependent children received 5 shillings and sixpence for a few weeks in 1848.

Migration in and out of the village

We tend to think of rural villages of the past as stable, unchanging places. By Victorian times, however, agricultural poverty and the growth of industrial towns saw increasing migration of families out of the countryside into the towns. This happened in Crakehall, where the lure of work in the towns and coalfields of County Durham and the West Riding drew people away from the village. More unexpectedly, families also moved to the village, so that although the population declined , as described above, new families moved into the village to replace at least some of those who had left. Moreover, as the 19th century wore on and the railways provided easy long distance transport, people came from much further afield. The extent of the resulting changes in family names found in successive censuses of the village is remarkable. I have analysed this migration, from the censuses taken between 1851 and 1901, and you can read about it HERE.

The influence of the landowners

For at least 250 years the village had no resident lord or squire. Since it was part of the Parish of Bedale there was not even a vicar or rector. When the yeomen wanted to enclose the open fields of Great Crakehall, they had to call on the support of Sir Timothy Whittingham of Cowling Hall, who had one small farm in Crakehall, for the necessary influence with the Court of Exchequer. The return of the manor of Great Crakehall to the local ownership of the Places and Goddards in the late seventeenth century, culminating in the building of the Hall and the occupation of Miss Turner and Matthew Dodsworth, must have made a real difference to the life of the village. It no doubt encouraged some of the more prosperous families to 'gentrify' their houses - Crakehall House in Great Crakehall, the "Malt Shovel" and the elegant pair of houses opposite in Little Crakehall, date from this period. For the first time there would be employment in the village for domestic servants and gardeners (Pickering and Dodsworth were the only inhabitants to pay servant tax in the early eighteenth century). The largesse of the Squire smartened up the green and the estate cottages in line with current fashion.

The enclosure of the common fields of both villages and the passing of Great Crakehall into private ownership had a further important effect on the life and status of the villagers. Enclosure meant that individual farmers could fence and cultivate their land as they pleased and this in turn made it simpler and much more worthwhile to buy and sell relatively small pieces of land, and to build houses there. The private landlords of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were also more inclined to sell small freehold properties than the crown had been. As a result, there was a rapid increase in the numbers of villagers owning their own homes and some land, particularly during the eighteenth century in Great Crakehall. The Land Tax returns show that by the second half of the eighteenth century there were at least 20 owner-occupiers in the village, many of them with only very small pieces of land - one field or a garth behind their house. In 1760 the Call Book of the manor records 38 families owning freehold there, though some were not resident in the village. By 1800 there were 25 owner occupiers of varying status - while Squire Dodsworth paid £5-10s in land tax and Christopher Pickering £6-16s, 16 freeholders paid less than 5s.

3. Education

Before the state began making grants towards the cost of education, attendance at school was voluntary and entirely at the parents' expense. Even the charitable Grammar Schools, such as the one in Bedale founded in 1588, were for the privileged few. At the end of the seventeenth century many of the witnesses to wills, and appraisers of probate inventories, could still not even write their own names, and "made their marks" instead on the written documents. By the start of the nineteenth century there are records of the most prosperous farmers sending their sons to local boarding schools, such as one in Barningham. There were, too, small "Dame Schools" , which taught the rudiments of the "three Rs" to village children for modest fees. By the 1780s Mr George Rymer had a school in Bedale with over 90 pupils, including children from Crakehall. William Hird of Bedale was one of his pupils and later described the school day in his diary. Lessons started at six in the morning! After an hour's break at eight o'clock, school continued until 1 pm.On Thursday and Saturday we wrote dicates from Aesop's fables, or letter book. Those who made the fewest errors received applause, the others a caution to mind better

Mr Rymer occupied the rest of his time as a land surveyor, and was responsible for laying out the route of the new road across Rand in 1784. In Baines' Directory of 1823, George Boddy is listed as a schoolmaster in Crakehal. A Mr Story was a schoolmaster there in 1839; his widow, Margaret, was still teaching there in 1851. Miss Arabella Eden, formerly a children's governess, had a Day School in Little Crakehall the mid 1850s to at least 1861.

The marriage registers for Crakehall Church begin in 1843, and from that date we can count the brides and grooms who could sign their own names. This gives a rough idea of literacy rates (though how much else they could write is another matter). By decades the figures are as follows:

| Years | 1843-52 | 1853-62 | 1863-72 | 1873-82 | 1883-92 | 1893-1902 |

| Number of Marriages | 49 | 55 | 40 | 41 | 37 | 28 |

| Illiterate | 27 | 20 | 13 | 10 | 5 | 0 |

| % Illiteracy Rate | 28 | 18 | 16 | 12 | 7 | 0 |

The present village school was opened as a voluntarily aided Church of England school in 1852, to cater for up to 100 scholars. You can find more about the school building, and see some pictures of the schoolchildren, in the section on Schools below. Children attended between the ages of five and twelve, and in some years as many as 80 pupils were on the roll. After the introduction of free education to the age of 14 in 1891 pupil numbers increased again. There were 86 scholars on the roll in 1898. This increased to 127 in the following year and an additional teacher, Miss L. Bramley, was appointed. Since it was a Church of England school, the parish had to pay for maintenance of the building and any other costs over an above the value of the annual government grant, whose size depended on the report of the Inspectors for the previous year. In the 1890s a voluntary rate of 3 pence in the pound was paid by property owners in the village to help with its upkeep. Nevertheless, income was sometimes inadequate for the increasing numbers of pupils. In 1899 the vicar appealed for more voluntary subscriptions, pointing out that if the school was forced to become a Board School every ratepayer in the Parish would be taxed . He wrote in the Parish Magazine in February 1899:

Many of the poor who are now rejoicing in the benefit which the abolition of the payment of school pence has conferred upon them, would find that the addition of the local rates which they would be compelled to pay, whether they had children to be educated or not, placed them in a worse position than when they were paying each week for their child's education. This consideration may well quicken the charity even of those who from political considerations desire to crush the voluntary system and make Board Schools universal.

Some idea of the teaching in the school a hundred years ago can be gathered from the Log Books and Inspectors' Reports . In June 1898 the Inspectors reported:

Discipline, Organisation, Singing by note, Needlework, Geography and object lessons earn the highest possible grant. In the Infants' Class: the examination was passed satisfactorily in the elements of Reading, Writing and Arithmetic, but occupations are not sufficiently varied and object lessons are almost neglected. If the highest grant is to be paid under article 98(a) of the Code, the children must never be left under the charge of a monitor. ...... The religious instruction is well cared for and the children showed interest and intelligence in the examination. The written work was accurately done

The Infants gave recitations of "The Ass"; "To school, to school"; "Playing at houses"; "My little sister"; "The clucking hen". The older girls recited "Father is coming"; part of "May Queen" and "Prisoner of Chillon".

With the increase in the school leaving age to 14, most children stayed at Crakehall school throughout. However, by the 1920s a steady trickle of children were winning scholarships and travelling each day by train to Northallerton Grammar School. Since the new comprehensive school was built in Bedale in the 1970s all the children have gone there up to the age of 16, with some going on to sixth form college in Northallerton. In recent years falling rolls threatened small village schools like Crakehall. Crakehall was fortunate in being designated as the centre of education for 5-11 year-olds from Newton-le-Willows and Patrick Brompton, which lost their own schools, as well as for Crakehall children.

4. The houses round the green

The map to accompany Aaron Rathbone's 1624 survey of Crakehall and Rand can not now be located, although the beautiful map of Rand survives in the Beresford Peirse archives. Nevertheless, because of the meticulous way the position of every tenant's house is described in relation to its neighbours in the written Survey it is possible to piece together the pattern of houses, cottages and garths around the village green at the start of the seventeenth century. These are shown in the MAP below. You can see a picture of one of the entries from the Survey, with a transcript into modern English showing how the village was described, HERE.Though few of the buildings of that time survive, their sites and garths do, and a map made in 1624 would look very similar to the Ordnance Survey plan from the start of this century - as we have already seen, the population changed very little during the 18th and 19th centuries, so there was little need for extra houses. In fact, as described in Chapter 1, we can be fairly sure that this main outline of the village dates back much further than the 17th century, for several features of it, such as the 15th century house now called Manor Farm, the Chapel Garth behind Crakehall House, the communal bakehouse and the lines of the roads and lanes hark back to medieval times. The present arrangement of house sites around the main green probably closely follows the plan laid out in Norman times for the 30 tenant families in the feudal manor, and the present boundaries of the garth ends undoubtedly date back to that period. The "West End" extension of the green may be a later planned extension to accommodate the growth in population late in the 15th century. This obviously continued in later centuries because the first edition of the Ordnance Survey map, and the Victorian census returns reveal many extra cottages and outbuildings crammed in behind the ancient sites. The present properties on the south west corner of the main green, including the disused chapel, are encroachments onto what was part of the green in the seventeenth century. Another encroachment is the house that is now at the western end of the row facing the church. It was only built late in the eighteenth century, and until then there was a much broader entrance to the Bedale road.

We can get some impression of what the houses and cottages were like, after 1600, from "probate inventories" made on the death of their occupants. About 50 of these have survived for Crakehall from the period between 1600 and 1700 (view a list here). A few of them describe the house contents room by room, and we can discover where the houses were in the village from the 1624 survey:

Taylor House

In 1623 William Ward, a tailor, died and his cottage was leased to Jane Jackson, the widow of William Jackson junior (see more about William Jackson here). As the abstract of the 1624 Survey on the previous page shows, it occupied "Taylor Garth", in the corner of the green beyond Crakehall House, and from the inventory of William Ward's goods it must have been very small and simple - he had a cupboard, an "awmery", a desk, a chest, two beds, one table, two chairs, a form, and various kitchen implements. By 1662 Robert Jackson, Jane Jackson's son, had bought the house and built a new one on the site. He left to his wife "the house wherein I now live, with one lathe or barn formerly called Taylor House.....". The new house had a "forehouse" - the living room with the main fireplace - an upper parlour, a low parlour, a "chamber" or bedroom and milkhouse; there was also a stable, as well as the old cottage preserved as a barn.

The Clapham house

At the opposite side of the green, near the present Methodist Chapel, was the Clapham house, only finally sold by the family in 1829.

The inventory of Robert Clapham, on his death in 1664, describes the house, as it was then, very well:

An inventory taken the 27th day of December in the year of our Lord God 1664 of the goods and chattells of Robert Clapham, late of Great Crakall in the county of Yorke deceased as followeth viz:

Inprimis his purse and apparil £2 - 0 - 0

Item In the forehouse one table, two plancke formes, one joynte settle, one cubhorde, one glassecase, nyneteene peeces of puter whereof eight puter dishes and the rest of pottengers, candlestickes and cupps, two brasse ladles, one broyleinge iron, a shreeinge knife, two joynte stooles and some other small implements

£2 - 10 - 0

Item In the parlor one canope bed, fower chests and coffers, one panell chaire, two flagons, one chamber pott, five small peeces of puter, five payer of sheets linninge and harden, two board cloathes, fower table napkins, fower quishins

£2 - 10 - 0

Item In the chamber over the house and parlor one panell chest, one trunke, one stockebed with a chaffe bed, two coverletts, three bolsters, one kimlin, one doughtrowe and other small implements to the value of £1 - 10 - 0

Item In the lowe parler one little table, three bolesters, three bed coverings to the value of £0 - 6 - 8

Item In the kitchinge one brasse kettle, one brasse pan, two brasse pots, one iron spitt, one salt cheste, one maskefatt, one old swinetubb, one stand, two payles, one swill and other implements to the value of £1 - 13 - 6

Item In the buttery one hogeshead, six barells little and great, one guilefatt, in ale and malt £4 - 0 - 0

Item One sowe and three shoates, one hen and five chickens, one goose

£1 - 6 - 8

Item for workegeare for wright worken £0 - 10 - 0

_________

£16 - 7 - 0

A gentleman's house

A distant kinsman of the Crakehall Jacksons was Thomas Jackson, a Bedale merchant who at various times owned part of the manor of Bedale and the Manor of Cowling. After selling Cowling, Mr Jackson retired to the house in Crakehall that his family had leased from Coverham Abbey for several generations.

This house, whose 18th century successor, Hall Farm, is shown in the picture above, now facing the Church, is interesting because it is the only "gentleman's" house that we have any information about. The appraisers for Mr Jackson's probate inventory listed a kitchen, a parlour, a chamber over the kitchen, a "lodgeinge chamber", the high chamber (which was being used as a store-room) and a barn. This sounds no more elaborate than Robert Clapham's, but the furnishings and his other possessions reflected Thomas Jackson's status - he had silver plate and silver spoons worth £12, three quarters of the value of all Robert Clapham's goods. A chest in his bedroom contained 3 pairs of linen sheets and two dozen table napkins, as well as tablecloths and pillowcases. There were curtains at the windows. Even so, furniture was sparse - a little table and two little stools in the kitchen, a table, form and six stools in the parlour, a bed , two cabinets and a desk in the bedroom.

A tradesman's house

The inventory of Henry Mason, a weaver who died in 1672, makes in interesting comparison with those of the prosperous yeoman farmer and the retired merchant.

In the forehouse one cubart, two tables, one chare, two shelfes, fower dublers, one kettle, one pan and other implements.

In the shope two lumes, one bedd, one whele, one doughtrough, one planke

In the parlor three chists, one chese press, two pare of sheets, two bedwares and two t owels, a happin and a coverlett, six pare of weaver geares and a shittle and other things belonging to that trade

In the barne six quarters of barly, a bedstead and a spinning whele.

In the shope two lumes, one bedd, one whele, one doughtrough, one planke

In the parlor three chists, one chese press, two pare of sheets, two bedwares and two t owels, a happin and a coverlett, six pare of weaver geares and a shittle and other things belonging to that trade

In the barne six quarters of barly, a bedstead and a spinning whele.

Although the arrangement of the houses around the green in the 1624 survey is easily recognisable today, the view of the 17th century village green was different in an important respect. A row of 7 houses and cottages ran along the eastern side now occupied by the Hall, its gardens and outbuildings. One or more of these might have been the remains of the ancient manor house or "capital messuage" but there is no documentary evidence for this. Very early in the 18th century the Goddards built part of the present Hall and must have incorporated or demolished three of the houses on the site. In the 1730s Mary Turner enlarged the Hall, adding the present front and making the gardens, stabling and old laundry as we see them today. It is recorded that she bought and demolished the remaining cottages on that side of the green to make way for her new development.

5. The green

The trees that are still such a delightful feature of the green are successors of ones that date back at least 250 years, to Mrs Turner's time at the Hall. The great sycamore (locally called a plane tree) that was felled in 1986 was known as the Queen Anne Tree, which would have dated it to the early 18th century, an age confirmed by a count of its growth rings when it was cut down. William Hird recorded another old plane tree near the old bakehouse. The trees alongside the cricket pitch were in Hird's time (early in the 19th century) a double row of old elms, which were said to have been planted in Mrs. Turner's time by a Robert Beadley. They were shown in a painting of around 1825 belonging to Mrs. Thompson at the Hall. These were felled in 1881 by workmen from Clifton Castle after several were blown down and others made dangerous by a gale. Charles Dodsworth of Thornton Watlass, who owned a lot of land in Crakehall, was very annoyed that he had not been consulted about this as a matter of manorial custom. Mrs. Pulleine of Clifton Castle wrote to him

if you had been with us when we went there to look at the old elms....I feel almost sure you would have seen that burly 'Mr. Boreas' had already so powerfully excercised his manorial right upon them that there remained no alternative in regard to safety of life..

.

The Pulleines presumably replaced them with the trees we see today.

As well as being the place for sporting activities - cricket, quoits, knurr and spell - the green was common grazing land. In 1813 the manor court reiterated the rules about grazing: each householder was allowed to turn upon the green one cow or horse, or 4 ewes and their lambs, from 6 in the morning to sunset, until midsummer. Pigs, bulls, stallions and tups were excluded. The pinder was to charge one penny for a sheep, and fourpence for any other animal in excess of this, or that strayed off the green. He could impound straying animals in the pound whose remains are rapidly disappearing at the bend of the back lane near the bridge. Occasional animals could still be seen grazing on the green in the late 1940s.

A big change to the green has occurred at the north west corner, where the road leaves for the bridge. Here, in front of the present houses where there is now open grass, stood the smithy, the smith's house, and the common bakehouse (see Chapter 1). The smithy moved further down the hill sometime in the 18th century, but the bakehouse survived in a ruinous state until it was bought by William Croft, the butcher in Crakehall, and converted to a house. It was eventually demolished some time in the 1800s. The old village stocks stood nearby, but they too have gone.

6. The church

The most recent change to the green came with the building of the Church. Through most of its history Crakehall has been part of the parish of Bedale and althoughthe Church was built in 1839-40, for its first 20 years it only served a "chapelry" consisting of Crakehall, Langthorne and East Brompton. Until 1861 baptism marriage and burial services continued to be the prerogative of the Rector of Bedale, and church rates were paid to Bedale. However, the churchyard was available for burials - the oldest gravestone in the churchyard commemorates Margaret Firbank, who died on July 5th, 1840, at the age of 91. In 1861, with the permission of the Bishop of Ripon, the Rector of Bedale relinquished his parochial rights in Crakehall to the Perpetual Curate of Crakehall, Thomas Rudd Ibbotson, and the four and twenty of Bedale acknowledged that Crakehall was now a separate parish. Crakehall ceased to appoint a churchwarden at Bedale and took charge of all its own affairs. The first vicar, Mr Ibbotson, served for 26 years, at a salary of £100 a year. He was succeeded by the Rev. Thomas Melville Raven, who occupied the vicarage for the next 30 years. He was a noted local antiquary and also an enthusiastic photographer, with his own darkroom in the vicarage, constructed by Luke Sedgwick. Following his death in 1896, the Rev. Wyndam Beresford Peirse held the post for 3 years before his apppointment as Rector of Bedale.The Church of 1839 was built to the design of John Harper, at the expense of the Church Commissioners, on 2237 square yards of the green given by James Pulleine of Clifton Castle, the Lord of the Manor. The vicarage followed in 1842. The Church was a damp, cold building which, despite work to improve the heating in 1857, urgently needed internal renovation by the 1890s. Soon after becoming vicar, in February 1897 the Rev. Beresford Peirse called a public meeting in the schoolroom to discuss fundraising for church renovations. He had received a report from the architect, Hodgson Fowler, that identified the replacement of the seating and floor as first priorities and recommended improvements including the insertion of an arch into the square opening to the chancel, two small windows, one into the sanctuary and the other over the font, and an oak altar rail to replace the cheap painted iron one. The builder, H. Harwood of Manfield near Darlington, estimated the whole cost at £455, which would have to be borne by the parish.

Mr Fowler's priorities were confirmed when the old pews were taken up and extensive dry rot was found in the floor. The church magazine reported:

their state certainly dispelled the illusion that the Church would have served its purpose for any length of time, the joists were so completely rotten that the workmen were surprised that the floor on the South side of the Church had not long ago subsided.

Every house in the parish received an appeal from the vicar for donations, while the ladies of the parish immediately began planning a fund-raising bazaar. By the end of the year individual subscriptions amounted to £319. In the straitened economic circumstances of the time, successful fund raising depended heavily on the local "gentry". The parish was, perhaps, fortunate in having such a well-connected vicar. The Beresford Peirses of Bedale, the Dodsworths of Thornton Watlass, Mrs Michell and her brother Colonel Garrett from the Hall, the Duke of Leeds from Hornby, Mrs Robson from Crakehall House and his Hutton-Squire relatives from Holtby Hall, Miss Elsey from Patrick Brompton Hall and the Lady of the Manor, Mrs Cowell from Clifton Castle, between them contributed over £250. Although 35 villagers also donated what they could, it amounted only to an additional £6. The village's main effort went into two money-making events - a grand two-day Silver Jubilee Bazaar at the end of April, 1897 and a sale of work in September 1898, each of which raised over £65.

The Silver Jubilee Bazaar was a great event, vividly described in the church magazine, "for which so many have been working for several months and to which others have been looking forward with mingled feelings of hope and anxiety". The stalls were in a large tent erected in the field behind the vicarage. Lady Cowell presided over a large stall "containing a supply of useful and ornamental articles of every description" . Mrs Robson and Mrs Hutton-Squire had a rival stall with "all manner of fancy goods and nick-nacks", while two farmers' wives, Mrs Hudson and Mrs Leake "provided a bountiful supply of useful and fancy work". Miss Wood and Miss Hood ran a basket and flower stall, and the Parish Stall sold "plain needlework and garments of all sorts, which had been made by the Parochial Ladies Working Party......which realised a substantial sum and have still a large quantity of goods for sale on some subsequent occasion. Mrs Michell's stall, which was opposite them, offered great and varied attractions, and was almost completely despoiled of its treasures by the conclusion of the second day's sale". The Beresford Peirse children managed a bran-tub and Lady Dodsworth was much occupied with her camera, taking portraits which were later exhibited for sale in the Post Office [ I wonder if any of these survive and can be identified? ]. The corner of the tent held the refreshments stall, which "became very popular about 4 o'clock, where for the modest sum of sixpence it was possible to get quite the best tea one could wish for. The whole of the contents of this stall were the gift of friends and neighbours....in fact nearly every house in the parish sent some contribution". A stage had been set up in the schoolroom, where a farce entitled "A Pair of Lunatics" was performed several times, together with music from the schoolmaster, Mr Callow, and his family. In the evening of the second day there were songs and recitations, followed by "an excellent ventriloquial exhibition by Professor Morgan of Newcastle". Competitions were also held, including a hat-trimming contest for men only "though it produced a small number of entries", and a washing competition. Sixteen competitors entered this, "each provided with a dirty duster, a cake of Sunlight soap, and a pail of cold water" and 3 minutes in which to complete the wash. "After a close scrutiny the judges - Mrs J. Pinkney and Mrs Linskill- awarded the first prize to Miss Farrow. Mr Ernest Beresford Peirse and Miss E. Kettlewell were second and third. The prizes were generously provided by the proprietors of Sunlight Soap and consisted of 12 plated spoons and sugar tongs enclosed in a handsome velvet case, and a quarter hundredweight case of Sunlight Soap".

The Church reopened on Easter Day, 1898, with the pretty window near the font, for which the children of the village raised £10-15s-9d, commemorated by an inscribed brass plate. The new altar rail, a new brass lectern, stained glass for the east window, a new font, an organ and a clock for the bell turret remained targets for future work.

7. The school

NOTE:You can find bigger versions of the school photographs shown here, and others, in the "People collection 1" section of Pictures. If you can identify anyone in these photographs I would like to hear from you.

The youngest schoolchildren and their teachers on a beautiful summer's day on the green. Possibly about 1910.

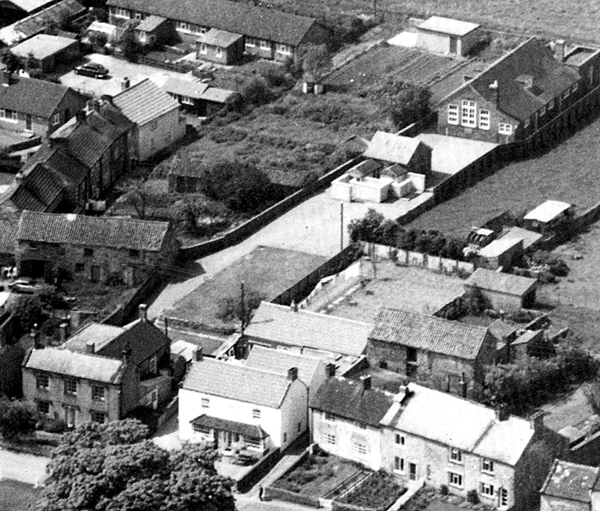

The school (and master's house, bottom left) in the aerial photograph below, was built in 1852 by subscription and a grant from the Diocesan Education Societies.

It had a classroom and a small Infant room, heated by an open coal fire and lit by paraffin lamps. As described earlier (see HERE), at the end of the nineteenth century it had a large number of pupils and there were repeated reports from the Inspectors about the lack of adequate space for the Infant class. A plan to extend the school westwards at a cost of £150 was abandoned because of lack of funds, but the decayed wooden floor had to be replaced urgently with a new concrete and wood block one by Luke Sedgwick for £9-15-0. The Vicar, not given to levity, wrote in the Parish Magazine that the floor was no longer in danger of giving way under its daily weight of learning.

The schoolmaster's house, about 1930

The present school building, seen top right in the aerial photograph above, replaced the old one in 1912. The original building became the Village Institute in 1912, and later the school dining room and kitchen. As the Village Institute it had a full-sized billiard table in the large room and a small one in the Infants room. Acetylene lighting was installed to illuminate the tables. The vicar, Mr Oliver, Mr Ackroyd and Mr Robson and Mr Wells the stationmaster managed a regular youth-club there. The new school building was big enough to accommodate more ambitious village activities, including drama, pantomimes and variety performances. A painted backcloth used on many of these occasions is in the collection of village mementos assembled by Mr G. Pocklington.

The photograph below is of the school pantomime, with suitably patriotic costumes, in 1940, kindly provided by Eric Walker.

A lot of information about the Church and the Victorian school in Crakehall was provided by copies of the monthly Crakehall Parish Magazine for the years 1897-1900. These unique survivals were found in Bedale Church in the 1980s by Mr R Taylor, when he was compiling an inventory of the church. The magazines were bound in three volumes together with the magazine of the SPCK. I believe they were subsequently deposited in the North Yorkshire Record Office, Northallerton.

8. Rebuilding the village houses

Around the green, and along the street to Little Crakehall, new stone-built houses were beginning to replace the old timber-framed and thatched houses by the end of the 17th century. Surprisingly, none of the houses seem to have date stones (though Bogg's early guidebook to Wensleydale said there were several), but architectural style and the written evidence of deeds and surveys give clues to the rebuilding of many of the village houses in their existing garths or crofts, between 1700 and 1750.

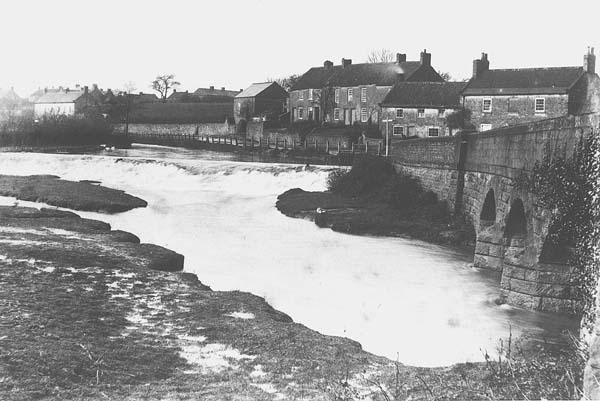

Slightly later, the house below Kirkbridge Mill was "newly erected" in 1795, while the row of cottages approaching Kirkbridge (see to right) were built as workers' cottages for the mill in 1812.

Public buildings start to appear after 1800 - the bridge, which replaced a wooden footbridge and ford shown on Jefferies' map of 1778, was built in 1829, the church and vicarage in 1840, the school and headmaster's house in 1852. The old Methodist churches by the bridge and in West End were built in 1839 and 1855. An earlier chapel was situated facing the beck at the western end of the present cottages between Great and Little Crakehall. It was demolished to make way for the the new road up the hill, by-passing the Malt Shovel, but can be seen in this early photograph of the village.

The cemetery chapel on Greengates lane was built soon after 1890.

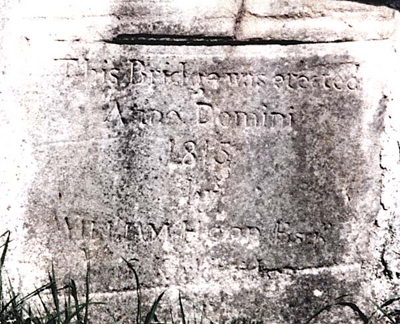

Before the proper organisation of local councils, much of the improvement of the village had been carried out by public-spirited gentlemen of the neighbourhood. At Kirkbridge Mr. Powell cobbled the old bridle track to Rand as a route to church and market, and Mr. William Hood erected the old bridge there in 1813.

The stone plaque commemorating this was incorporated into the nearby wall when the council rebuilt and resited the bridge in 1958.

At about this time, too, the more prosperous inhabitants of Little Crakehall improved the hill on the old road in front of the Malt Shovel, easing the gradient by making a cutting and building the fine stone retaining walls there. The new road to Little Crakehall was only constructed in this century, by the local authority, which also raised the level of the road along the beckside, and constructed the present weir above the bridge. Until that time the beck spread into the field on the far side, where the old embankment can still be seen. Just above the bridge it divided into several rivulets as it tumbled roughly down to the bridge, using all the arches. The road up to the green from the bridge had been smartened up in the early 1800s by Thomas Sadler, who renovated the house and cottage at the corner of the green (Bridge House) and rebuilt the house by the beck-side (later the Crown Inn, then an unlicenced Guest House and finally a private house, Brookside). He made the high stone wall and planted the trees behind it. His work probably included the erection of the iron railings around the ancient St. Edmund's Well, so badly neglected last time I saw it.

The retaining wall and railings alongside the beck at the top of the Kirkbridge lane appear to have been built at the same time as the improvements to the beckside in Little Crakehall - they use the same stone uprights and tubular iron rails. One of the stone posts there is a reused direction post from the Great North Road. Two other old stone direction posts, more or less in their original locations, are at the Kirkbridge end of Greengates lane (dated 1793) and at the junction of Scroggs Lane and the road to Newton le Willows.