1. The ancient manors 1084-1600

The Domesday Book shows that Crakehall was a well established Anglo-Saxon settlement before the Norman conquest, and names the two chief men there - Ghille and Ulchil. It records that there were already two manors in Crakehall in 1084 :In Crachele are 12 carucates for geld [tax] and 7 ploughs can be there......... Ghille and Ulchil had 2 manors there. Now 2 knights have it of the Count [Alan] and 2 ploughs are there on the demesne, 8 villeins and 6 bordars (cottagers) with 5 ploughs, and 1 mill of 4 shillings [annual value]. 8 acres of meadow. Pasturable wood 2 furlongs in length and as much in breadth.The whole manor has 1 league in length and 1 in breadth. [At the time of King Edward the Confessor] it was worth 40 shillings; now it is worth 38 shillings.

The early Norman lords of the manors of Great and Little Crakehall are shadowy figures, knights rewarded with lands in England in return for their military services to King William and his Counts. They owed their feudal alliegiance to the great Honour of Richmond, comprising most of the North West of the North Riding. This had been granted by King William to Count Alan of Brittany, who in turn awarded part of it to his brother Ribald. This part included Middleham, Coverdale, the southern side of Wensleydale, and the outlying villages of Crakehall and Well. Ribald built Middleham Castle, originally on the motte and bailey behind the present castle, and his descendants remained Lords of Middleham until the 14th century. Throughout this time, and into the 17th century, Great Crakehall remained part of the Lordship of Middleham, under the direct control of the Lords of Middleham.Amongst Ribald's estates, Crakehall is unusual in being valued as highly in the Domesday survey as it had been before the Norman invasion. Nearly all the rest were still very run down following the army's "wasting of the North" a few years earlier. This has led historians to suggest that Crakehall was deliberately planned by Ribald for the resettlement of displaced people from further up the Dale, because of its advantageous site and agricultural potential. The square green surrounded by its houses may have been laid out at that time.

For the most part, the beck is the boundary between the two manors. However, the tenants of one farm and three cottages in Little Crakehall always owed their manorial duty directly to the Lords of Middleham and the fields allotted to them when the Little Crakehall common fields were enclosed became part of the manor of Great Crakehall for administrative purposes. In addition, the great 1624 survey ( see HERE) shows that the water meadows immediately on the north side of the beck downstream of Great Crakehall were part of the Manor of Great Crakehall, suggesting that this was the first settlement which hung onto the most valuable waterside land when Little Crakehall was settled as a separate manor. The low-lying area in which Crakehall Ings lies was open meadow shared by the manors of Langthorne and Great and Little Crakehall, and remained undivided in 1624.

Little Crakehall, which may have begun simply as an outlying farm of Crakehall (like Rand) at a very early date, seems to have been granted to a feudal tenant, who took the name Crakehall as his surname. During medieval times this family became very prominent in northern circles and their names are found as witnesses on many official documents and deeds of the period. They held their own manor court in Little Crakehall, but no records have survived. By the end of the 14th century the Crakehall family were rich merchants in York, and they had sold their manor before 1426 to Christopher Conyers of Hornby Castle, whose heirs retained it until the start of the 17th century. During that time we have virtually no documents concerning Little Crakehall, and it only appears again in the historical record when deeds record the sale of individual farms there and in Langthorne to their tenants around 1610. There is no further record of a manor or manor court in Little Crakehall, and when the Crown was pressing for enclosure of the common fields there in the 1600s they dealt directly and exclusively with the individual freeholders of the farms.

The manor of Great Crakehall, usually simply described in documents as Crakehall, is much better recorded. Soon after 1310, Mary of Middleham, the last direct descendant of Ribald, married Robert Neville, heir to the great estates of Raby and Sheriff Hutton. This established one of the great dynasties that dominated the north for the next 150 years. They established a market outside their castle walls at Middleham in 1389. The "West Road or Moor Road" from Crakehall across Nomans Moor to Ulshaw Bridge represents the old route there from Crakehall, but there had been a market in Bedale since 1251, and it is uncertain whether Crakehall people would have been forced to use Middleham. In 1473 Lady Anne Neville, heir of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, married Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the future King Richard III. In turn his property was confiscated by Henry III following Richard's defeat in the Wars of the Roses, and the Lordship of Middleham became the Crown estate it was to remain until 1624.

Thus the history of the feudal manor of Great Crakehall is that of the Lordship of Middleham for 500 years. However, during Elizabeth Ist's reign things were starting to change. Elizabeth was keen to increase revenues from her northern estates but in the Lordship of Middleham she was constantly frustrated by the form of farm tenure, 'copyhold' , enjoyed by her tenants there. This gave tenants the absolute right to transfer their tenancies to their sons on payment of a small fee (a 'fine') to the lord of the manor, and without any increase in rent. Elizabeth made several attempts to overthrow this system, but it was so well rooted in manorial custom that this was impossible without the agreement of the tenants. It was not until 1601 that she was able to replace this customary tenure by 40 year leases, but even then the rent increases imposed were minimal. One of the most valuable assets of the manor, the mill, was sold to the sitting tenant John Dodsworth, but otherwise the crown gained little by the change.

Twenty years later, following the enclosure of the open fields, the manor of Great Crakehall was sold by the Crown to two brothers, John Ramsey and Robert Ramsey of London, "at the request of the Earl of Holderness". The Earl of Holderness, another John Ramsay, who was also the Earl of Haddington, was presumably a relative of theirs.

2. The monasteries and their property in Crakehall

Although the Lords of Middleham were the lords of the manor of Crakehall, they were not the only landowners. From the earliest times records show a few families, notably the Drurys, owning small freehold estates there (probably granted as rewards for service as officials of the Honour of Richmond). Much more important for the future history of the village was the property owned by the Premonstratensian Canons at Coverham and Easby Abbeys. The Lords of Middleham were great patrons of Coverham Abbey. They granted them the site at Coverham when the Canons moved from Swainby in 1214, and they supported the abbey with further grants, especially after it was ravaged by the Scots in 1315. In 1316 Mary Neville established a chantry chapel in Thoralby in Wensleydale, at which priests from Coverham Abbey were to pray for Mary's soul and hold a service each day. To support this she gave the Abbey four farms, 19 acres of her demesne land and four and a half acres of meadow in Great Crakehall. Her son granted a further 61 acres of land in Crakehall, promised by his mother. In 1341 the Abbey received yet another gift of property in Crakehall, from Edric of Newton and John Wensley, chaplain, consisting of four farms, 6 cottages, 75 acres of arable land, 26 acres of meadow and 5 acres of pasture. We do not know who Edric and John were, or how they came to have the property they gave to the abbey. It is possible they were simply acting as intermediaries for the Nevilles. As a result of these gifts, by 1341 the abbey owned 8 farms and 6 cottages in the village. As far as we can tell they never had a monastic grange in Crakehall, but simply let the farms and cottages to tenants, who remained under the jurisdiction of the lord of the manor. The Abbey's land was scattered in the open fields of the village and therefore can not be identified as a distinct part of the village. Unfortunately, the ancient records of Coverham Abbey have disappeared. However, we have a survey of their property in Crakehall made in about 1600, before the Crown sold it (see HERE), and the positions of some of their houses around the village green can be identified from the 1624 survey (see MAP), and this shows that they, too, were scattered around the village.Easby Abbey owned one small farm, in Little Crakehall, given to them by William and Alan de Crakehale, lords of Little Crakehall. The charter is recorded in the Cartulary of Easby Abbey (for the full reference see HERE) and is particularly interesting as it gives some of the earliest field names we have for Crakehall (see FIELDNAMES HERE). Several of these names were still in use in the 19th century and the fields can still be identified on the ground today (see FARMING).

Coverham's and Easby's lands in Crakehall were confiscated by the Crown when the monasteries were closed by Henry VIII (for the full reference see HERE), and continued to be let individually for the rest of the 16th century. Around 1610 the Coverham land was sold to Sir Richard Theakston, of Theakston near Burneston, a crown official in the North Riding. He bought the manors of Burneston and Bedale at about the same time. Abraham Cartwright inherited the Theakston estates and in 1624 it was reported :

The heirs of Abraham Cartwright Esq. holdeth freelie ..... eight severall tenements and divers lands thereunto belonging with the appurtenances late Sir William Thexton's, sometime parcell of the possessions of the late dissolved Abbey ...

The Place family of Well bought most of the property sometime between 1624 and 1667. The Easby Abbey land was sold with the manor of Crakehall in 1624.

3. Landlords and the manor from 1600

The sales of the manor of Great Crakehall brought the end of an era for the villagers. Instead of the powerful nobility, the landlords from now on were 'landed gentry', many of whose families had acquired their wealth through success in the professions or in business. Although Great Crakehall had been granted to the Ramsey brothers, the property seems to have constituted a trust for Sir Robert Heath. Sir Robert was a staunch supporter and financier of Charles I and was Lord Chief Justice of Common Pleas in 1631. He appointed a steward, John Wastell, to look after his Crakehall estate, and there is a record of him holding a manorial court there in 1638, but no evidence that Heath ever visited the village in person. He had little time to enjoy the proceeds of his new property. By 1638 he was in debt to the tune of £6250, a huge sum of money in those days, and he desperately tried to pay this off by selling and mortgaging his estates. However, the Ramseys and one of the mortgage holders refused to permit the sale of Crakehall. Further problems arose during the Civil War, when he continued to support Charles. His estates were confiscated by Cromwell during the Commonwealth and he was impeached, forcing him to flee to France where he later died. On the restoration of the Crown, Robert's son Edward recovered all his father's estates though these were by now heavily mortgaged. in 1667 he finally sold his Crakehall property, and the lordship of the manor, to Edward Place of Well, who already owned the old Coverham Abbey farms. Place was also busily buying farms in Little Crakehall from families who, a generation or two earlier, had bought their freeholds from Lord Conyers of Hornby Castle.

By the end of the 17th century the Places owned a large part of both villages,and the lordship of Great Crakehall. The written records of several of their Manor Courts survive (see one HERE). Thomas Place settled some of the Coverham Abbey farms on his son Henry, of Richmond, when he married in 1677. Henry subsequently inherited the rest of the manor of Great Crakehall, and in 1705 he sold it, together with the High Mill in Little Crakehall, to Edward Goddard of Richmond and his wife Elizabeth. The deeds of the 1705 sale record a "capital messuage" let to Christopher Bateman, with several cottages adjoining the orchard there. The rest of Place's property in Little Crakehall was settled on Edward Place's other son, Thomas Place, when he married Ann Maddison, the daughter of a coal owner in County Durham. Thomas became Recorder of York, and his property passed via his daughters to the Huttons of Clifton Castle in 1805.

On Edward Goddard's death in 1729 his estate was split into two parts. One share, including the Hall, the lordship of the manor and the greater part of the land, went to his elder son Darcy, who was an apothecary in Aiskew. However, the High Mill in Little Crakehall and two farms, High Scroggs and West Pasture, with a few other properties went to his son Henry, then a student at Cambridge, and subsequently to one of his daughters, Cordelia. They were sold to the Huttons of Clifton Castle in 1779, shortly after she had married William Withers, a York alderman. A particularly attractive map, showing several parts of the village, was made at this time and is now in North Yorkshire Records Office (Ref ZAW 243)

Darcy Goddard had little interest in his new estate. In 1732, three years after his father's death, he sold the lordship of the manor and remaining property to Miss Mary Turner, a member of the Turner family of Kirkleatham in Cleveland. Miss Turner bought up the remaining cottages on the Hall side of the green, and demolished them to enlarge and improve the Hall as her own residence. She spent the next thirty years as an admired and respected Lady of the Manor. She was responsible for the Hall as we now see it, and for the first planting of trees on the green, whose successors are such an attraction to this day. She reintroduced regular manor courts, for which she appointed local people to a number of traditional manorial offices. The manor court rolls of this time record its activities in great detail. Miss Turner's steward, Edward Bunting, drew up instructions for the officers, probably using the traditional forms of the manor judging from some of the archaic spelling and outdated customs:

Manour of Crakehall (Instructions to bailiffe)

These are to require you to summon all the tenants of the said manour, whose names are hereunder written,and all other persons that do owe suit or service to the said Court personally to be and to appear at this Court Baron to be holden for the manour aforesaid, upon the 23rd day of October instant, at the house of John Whitton, carpenter, then and there to do and perform their several suits and services according to the customs of the said manour, and have you there the names of such persons as you have so summoned, and this precept given under my hand and seal this 23rd day of October, 1733.

These are to require you to summon all the tenants of the said manour, whose names are hereunder written,and all other persons that do owe suit or service to the said Court personally to be and to appear at this Court Baron to be holden for the manour aforesaid, upon the 23rd day of October instant, at the house of John Whitton, carpenter, then and there to do and perform their several suits and services according to the customs of the said manour, and have you there the names of such persons as you have so summoned, and this precept given under my hand and seal this 23rd day of October, 1733.

William Inman was the bailiff, and he summoned 75 tenants and freeholders to the court. The Steward was then to swear in a jury and foreman, and an officer responsible for collecting fines imposed by the court.

Miss Turner held courts regularly throughout her time as Lady of the Manor, until her death in 1763. The tradition was continued by her successor, Matthew Dodsworth of Thornton Watlass Hall. He became Lord of the Manor by virtue of his marriage to Miss Eyre, Mary Turner's niece and heir. He and his wife moved to the Hall at Crakehall and entered into the life of the village as enthusiastically as his predecessor. On assuming the manor he arranged a "beating of the bounds"; this was supposed to be attended by all the jurymen of the manor court. The next court fined one of their number, Thomas Johnson, 2 shillings for " not appearing to give his verdict and refusing to attend the rest of the jurors on their view, though he had notice for that purpose and was at home all day". Evidently Thomas did not share his landlord's regard for tradition! Dodsworth continued to appoint a Steward, Bailiff, Constable and Pinder, and gave them substantial powers. In 1786 the court fined William Plews no less than ten shillings and sixpence (several weeks' wages) for breaking into the pinfold "and releasing his goods, they having been put there by the pinder."

Matthew Dodsworth was a very notable man in the area - a Justice of the Peace and a very substantial landowner. He seems to have been the archetypal 18th century squire - fair by the lights of the time, but a stern upholder of the law as a J.P. and severe in his defence of his rights as a landowner. Early in his reign as a JP he acquired a reputation for severity by gaoling a poor Crakehall man, Joseph Benson, for illegally fishing in Crakehall beck. Benson died in prison and Dodsworth was widely criticised by the tenantry for cruelty, a reputation which his severe treatment of vagrants brought before him did nothing to dispel. However, in later years he seems to have taken a more flexible and robust attitude to petty offenders. The diary of William Hird of Bedale records that Dodsworth "oft took a kind course" by suggesting that disputants in court should retire to the local public house to make up their differences - "twas many a case he thus did stop and people got friendly" . His sporting activities, from cockfighting in the company of old Kit Collinson of Crakehall who "kept gamecocks fine" to prize-winning racehorses were also popular with the local people.

Perhaps not since the time of the Nevilles had Crakehall witnessed the splendour of living displayed by Mr. and Mrs. Dodsworth at the Hall. The squire and his lady made an imposing sight as they rode on horseback around the village, he with his white powdered hair, she in her fine riding habit and befeathered beaver hat. The household manservants wore livery -"a blue coat turned up yellow, and a yellow waistcoat, black smallclothes of shag or velveteen, and a silver-laced hat with a broad girdle". The staff were treated very well and were devoted to the family. Matthew Day, the butler, and Mrs. Haythorne the housekeeper, were at the Hall for many years and were a well known sight at the head of the servants in the Dodsworth pew at Bedale Church each Sunday. Squire Dodsworth was also a Captain in the North Yorkshire Militia and recruited many young men from Crakehall to its ranks, making three of them his NCOs.

Matthew Dodsworth died in 1804, a year after his wife, and through legal arrangements made by Miss Turner the manor passed to Mrs Dodsworth's heir, Anthony Hardolph Eyre of Nottinghamshire. However, Matthew Dodsworth had been very active in purchasing and exchanging land in Crakehall in order to consolidate his farms there (at least 17 deals are recorded in the Registry of Deeds between 1777 and 1822) and some of these farms seem to have been inherited separately by Francis Dodsworth of Thornton Watlass. Mr. Eyre had no interest in the estate and put it up for auction in 1805.

The Hall and the lordship of the manor were bought by Mr. Peirse of Bedale Hall but sold again in 1810 to Henry Percy Pulleine, who already owned the Crakehall property that the Goddards had not sold to Mary Turner in 1732. The Pulleines lived at the Hall for several years, but after Henry's son James inherited the Clifton Castle estate from his cousin Timothy Hutton in 1833 he let Crakehall Hall to a succession of tenants. James' daughter, Georgina, married General Sir John Clayton Cowell, Master of the Household to Queen Victoria. After his death, Lady Cowell took a keen interest in her role as Lady of the Manor of Crakehall and was an active supporter of village activities, such as fund-raising for the renovation of the Church. The Cowell's daughter married Vice-Admiral Sir A.G. Curzon Howe, and the Curzon-Howe-Herrick family subsequently held the manor until the 1960s. Crakehall Hall was occupied by a series of tenants, most notably Mrs Mitchell, the young widow of John Michell of Forcett Park who was living there with her father, the Rev. Garrett, in 1871 and who remained at the Hall until about 1905. It was sold in the 1950s to Mr. and Mrs. Thompson of Aysgarth School, Newton-le-Willows.

BELOW : Mrs Michell with her

favourite pony,

about 1900

The Pulleines held the occasional manor court until about 1860, but these became of little significance and the main importance of the "manor" became the ownership of the shooting rights! Subsequently some of its responsibilities became those of the Parish Council, which is recorded at the turn of the century considering such matters as the felling of a tree on the green, the dangers of motor traffic on the hill to the bridge, a local water supply (rejected as too expensive in 1923 and not installed until 1940) and electric lighting. Finally, in 1972, the Clifton Castle estate generously granted the remaining manorial rights in the village, essentially guardianship of the village green and the mill batts, to the Parish Council for a nominal fee. The Council now has the product of the local rate precept for communal expenditure and is a very active body, meeting every month to consider planning applications (in an advisory capacity) and such matters as footpaths, seats, childrens' swings and anything affecting the welfare of the village.

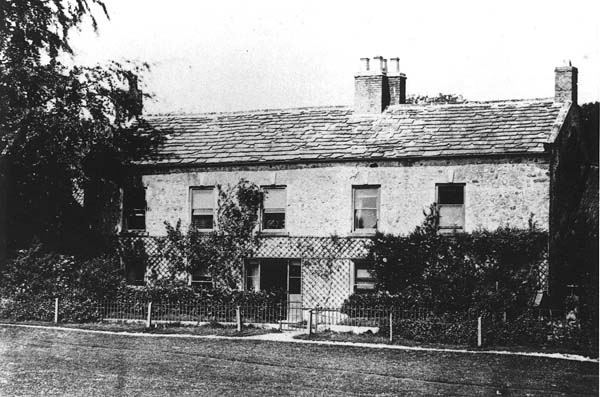

Apart from the Lords of the Manor, the Crakehall landowner who had the greatest influence on the development of the village as we see it today was Mr. Christopher Pickering, who lived at Crakehall House throughout the second half of the 18th century. He was High Constable for the wapentake of Hang East and a much respected gentleman of the "old school". He and his daughter were a familiar sight driven through the village by their coachman in a carriage and pair. They kept a fine house and gave the northern end of the village green its present appearance by fencing and planting the 'Chapel Garth' , in which the house stands, with fine trees. One of his daughters married a younger son of the Robson family of Holtby Hall and inherited the Crakehall property in 1804. Captain Robson and his wife subsequently lived in Crakehall House for many years.

Captain Robson's house

date unknown