1. Introduction

Most old documents that have survived are concerned with land and farming. It is only in the nineteenth century, when trade directories and detailed census returns appear, that we get a complete picture of work in the village other than farming. Baines's Directory of 1823 lists two millers, a linen weaver, a joiner and cabinet maker, a blacksmith, a shoemaker, a tailor/dressmaker, three shopkeepers (butcher, grocer, tallow chandler) and two innkeepers (at the Octavian and the Revellers). In Kelly's Directory of 1857 ( see here ) we find, in addition, a mason and bricklayer, a wheelwright, a brick and tile maker, a rope-maker and two dressmakers. The railway had arrived by this time , so now there is a Stationmaster listed as well.The following sections give the histories of the trades in the village that have left some documentary evidence behind.

2. The water mills

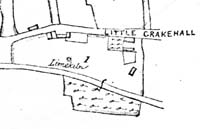

There have been three water mills in Crakehall; the High Mill in Little Crakehall and Kirkbridge Mill are now private houses, while Crakehall Mill (or the Low Mill), once the manorial corn mill, has been restored to working order. Mills were valuable properties and they feature prominently in old documents, making it possible to trace their histories in some detail.Crakehall Mill

High Mill

Kirkbridge Mill

Crakehall Mill - the manorial corn mill

The Manor of Crakehall already had a corn mill at the time of the Domesday survey in 1084. By 1298 the Lord of the Manor, Robert Tatershale, had added a fulling mill for treating cloth, one of the earliest recorded in North Yorkshire. The Inquisition Post Mortem of Robert's property ( see here ) valued the two mills together and their two functions may have been carried in the same mill building, as was common in the middle ages. At that time separate waterwheels would have driven the grinding stones and the fulling stocks. The gearing necessary to switch the power from a single wheel from one set of machinery to another only appears later in the history of watermills.[ For an excellent account of of the historical development of Yorkshire watermills, see Jane Hatcher's book "The Industrial Architecture of Yorkshire", Phillimore, 1985 ]. At various times in its life the High Mill was a fulling mill but there is no evidence that it existed in 1298. Subsequent inquisitions of the Lords of the Manor ( see here ) record the corn mill and fulling mill in 1367 and 1374 and the manor court rolls of 1450 ( see here) reveal their sorry state after years of national economic depression and depopulation. The court reported that the corn mill had a damaged lower millstone while the bailiff told them that "Thomas Rand, by the order and view of Ralph Skipton, for the lord, has between the last court and this one carried out repairs on the fulling mill (11 shillings)" and the lord had repaired the millpond wall. Despite this the mills remained unlet. A more complete renovation of the mill was carried out in 1466. The manorial accounts record payments to Thomas Harrison, carpenter, for work on repairing the wooden machinery inside and outside the mill, for 16 days at 5 pence per day. A wagonload of new timber was brought from Burstall Wood, and iron work was renewed. John Appulton and John Borell carted stone roofing slabs from Leyburn and sand and gravel from the Ure near Masham to repair the stonework and roof of the mill.

In 1538 the Crown leased the watermill in the Lordship of Crakehall to a Thomas Ley for 21 years, at £3 - 6 - 8 per year, and he sub-let it to Nicholas Metcalfe. Before the expiry of Ley's term, in 1554, the lease was transfered to Nicholas Metcalfe, again for 21 years. Metcalfe was given leave to take sufficient timber from the manor to keep the mill in repair. Jane Hatcher, who has made a detailed study of the building, suggests that at this period an old water wheel was replaced by two smaller undershot wheels whose axle holes and scars on the massive old stonework lower courses of the outer wall can still be seen. In 1592 John Dodsworth took over the mill on a new 40 year lease for £3-13-4d a year. The increase in rent on transfer of the lease was a convention of Crown leases and does not necessarily show that the mill had been improved. However, for the first time it is described explicitly as a corn mill, so there may have been two separate sets of grinding machinery by this time. When the mill was sold with the rest of the manor in 1624 it was valued at £4-6-8d a year.

By the time the manor was valued for the new owners by Aaron Rathborne in 1630 the mill was no longer part of the property. It was probably sold to the miller, John Dodsworth. His descendants are recorded as freeholders in the village for the next 100 years and probably built the miller's house. They advertised the mill to let in the Newcastle Courant in February, 1726:

Crakhall-Mill, in which are two Pair of Grey-Stones, and

one Pair of Blue, a Dwelling House and Stables, a Kiln for

drying and shilding Oats, all in very good Order and Repair,

with about 4 acres of Meadow Ground, near Beedal, Masham

and North Allerton and within a few Miles of Richmond and

Middleham.

Grey stones were used for grinding animal feed while "blue" stones, imported from the Rhine area, were for flour [ information from Jane Hatcher ]

According to the National Monuments Record (see here) the miller's house was built between 1700 and 1799. A later John Dodsworth sold the mill to Thomas Sayer, miller. His heirs sold it in turn in 1766 to the Dodsworths of Thornton Watlass Hall who were landlords of a substantial part of the village at the time. The property was then described as: a messuage, garden, stable and also the water corn mill

and the kiln belonging to it [i.e. the corn drying kiln]

known as Crakehall Mill, in the tenure of William Slinger.

In 1806 the Dodsworths sold the mill, the millers house and the field above it called Mill Hill to James Robson of Crakehall House, and Mathew Musgrave became tenant. The Musgraves had been millers for several generations and had, in the last 50 years, been tenants of the High Mill in Little Crakehall and of "Langthorne Mill" (which was almost certainly Kirkbridge Mill). They also built an additional storey to provide extra storage space. Outbuildings were added to the house, which was also modernised. In the late 1830s, Mathew Musgrave died and for a few years, until their son Leonard was old enough to take over, Mathew's widow Elizabeth employed first Thomas Clarkson, then John White to run the mill. However, by 1851 Leonard Musgrave was in charge. During the 1860s and 1870s the Musgraves seem to have worked in partnership with the Hobsons - John and his son William - who were also running Kirkbridge Mill in 1881. By 1881 Leonard Musgrave had retired and the Hobsons soon afterwards took over as tenants, leaving Kirkbridge. Bulmer's Directory of 1890 ( see here ) shows John Hobson, "corn miller and steam threshing machine owner" at the Low Mill. During the Hobsons' time the old wheel was replaced with a new iron wheel built by J. Mattison and Co. of Bedale (Leeming Bar) which still survives. It is dated 1897. ( See here for an interesting article about the wheel from the Darlington and Stockton Times ).

On the break up of the Robson estate, William Hobson bought the mill and mill farm, and the family remained at the mill house until Miss Hobson died in 1977, by which time the mill itself was unused and partly derelict. It had last been used in the 1930s and posed an enormous task of restoration when Colonel Whitaker Holmes bought it. This involved not only restoration of the mill itself, but dredging of the mill pond, which was completely silted up, and installation of new sluices. However, his drive and determination overcame all obstacles and by 1982 it was again in working order and open to the public. After Colonel Holmes retired, the mill was owned successively by Peter Townsend, the Gill family (see the newspaper article mentioned above) who had it for about 6 years and Penny Trott who was there for about 2 year. The present owners, Lionel and Alison Green, bought it in October 2004. At the present time (Spring 2007) the mill is closed to the public, awaiting essential skilled repairs.

The photographs compare the state of the millpond and sluicegate in 1970 (left) with the clear millpond (right).

The machinery which remained when Colonel Holmes bought the mill was of the spur-gearing type common in Yorkshire, thought to date from the late eighteenth century. It was designed to drive four pairs of grinding stones - two pairs of grey stones for animal feed and two French burrs for producing flour. The latter have survived in working order and one is inscribed 'W. Knowles, maker, Thirsk, 1850'. The other pair came from Mountains of Newcastle upon Tyne.

Crakehall High Mill

For many years the High Mill incorporated a fulling mill for felting cloth - variously described as a "warp mill, walk mill or crab mill". It probably served the linen weaving business at Kirkbridge Mill, as well as local handloom weavers.

A "walkmilne close" is recorded in Little Crakehall in the will of Thomas Clarke, made in 1626 ( see here ), but the first detailed records of this mill date from 1667, when Edward Place of Well, who was then Lord of the Manor of Crakehall, included it in his son Henry's marriage settlement. Neither the earlier records of the manor, nor of Coverham Abbey's property in Crakehall, mention High Mill, so it was either part of the manor of Little Crakehall, for which no documents survive, or was fairly new. However, there is no evidence that rules out the possibility of it being the medieval fulling mill mentioned in the manorial records. Thomas Clarke owned the "walkmilne close" in Little Crakehall in 1626 ( see here ) and in 1620 Richard Vittie was grinding corn at the "Walkmill" in Little Crakehall. You can see an inventory of his household goods, made in 1621, here. In 1677 the mill is described as "all that fulling mill called the Warp Miln, with the dams, clowers, wheels, coggs, axletrees......with such ground as John Musgrave doth therewith enjoy". Musgrave also leased High Mill Farm, with Cherry Garth and Broad Garth. The mill was owned at that time by the Goddard family, of Richmond, who had interests in other mills, including Whitcliffe Mill in Richmond. The family suffered considerable financial difficulties and by 1765 High Mill was in a rather dilapidated state. Miss Goddard then leased it to Johnson Moses, a fuller of Methodist family from Barnard Castle. They agreed that the owner should pay for modernisation of the mill and for the introduction of new equipment, both for grinding barley and for bleaching cloth. Moses obviously believed in diversification.

Johnson Moses also rented the farmhouse and 'several small closes of meadow or pasture known as the Bothams in which the mill and tenters are erected". The tenters were used for stretching and drying the cloth. In return for this investment the rent was put up to £24 a year. The receipt for the bleaching equipment survives: "a lead and copper bottom press and screw" costing £25. In his diary, William Hird of Bedale recalled Johnson Moses, by then an old man -

the old mill at Crakehall was called the Warp Mill, on account of woollen cloth being densed and milled here by old Mr. Moses and his son Joseph, a religious and pious family, and of the first here that were called Methodists. Besides the corn mill they had a crab mill and a large bleachyard. On market day we did them see, they brought a large pack load to the toll booth both soberly.

Receipts for work carried out at the mill reflect these diverse activities. For example, work carried out for Miss Goddard in 1778 included:

22 yards of Table Linnin bleached at 3d /yd

28 yards of Table Linnin bleached at 3d /yd

1 stone of fine pearl barley at 4s

34 yards of sheeting cloth at 2d /yd

The old mill is shown on estate maps of 1778 and 1810 situated on a short mill race simply cutting across the loop in the beck around the mill field. However, soon after 1810 this part of the Crakehall estate was bought by the Huttons of Clifton Castle, energetic and go-ahead landed proprietors keen to improve their estate. They rebuilt the mill, as a corn mill only, on roughly the same site and constructed a long mill race from the beck at the very westernmost edge of their property at Allerton Deeps about half a mile above the mill. This provided the big head of water required to drive the new overshot bucket wheel built by Henry Sugden Ltd. of Bramley near Leeds. The photograph shows the mill, unaltered, in February, 1971. The mill race enters along the top of the embankment and wall on the left. The tenter field is to the right.

28 yards of Table Linnin bleached at 3d /yd

1 stone of fine pearl barley at 4s

34 yards of sheeting cloth at 2d /yd

The excavated soil from the race forms the mound in the field between the mill stream and the Patrick Brompton road. Flow of water into the mill was controlled by a sluice a few yards above the mill, through which water could be diverted back to the beck. Much of the wooden machinery from the old mill was re-used, and drove four pairs of stones. A cog on the main shaft also drove a sack hoist, which was put into operation by a moveable roller that increased the tension in the drive belt. On the ground floor, wooden leavers were able to slightly separate the grindstones above , via iron linking rods, to release trapped foreign bodies. The waterwheel was so finely balanced that even in the late 1940s a few buckets of water poured into it were sufficient to start it turning. The new mill building was typical of those erected by Clifton Estate during the early 19th century. It included a grain-drying kiln with perforated tile floor to allow flow of warm air from the floor below, where a room had a fireplace and a chimney built into the thickness of the back wall. The slightly arched windows had cast iron frames divided into small diamond panes (all of slightly different sizes, as Mr. Norman Wilson discovered when he tried to replace some!). Corn was ground by water power at the mill until 1947.

For a short time in the 1840s, Leonard Musgrave was tenant there, before he took over the Low Mill. John Braithwaite then operated the mill until the 1860s. After a succession of short-lived tenants, John Simpson took over and was miller there until after 1901. One of the main structural timber beams on the upper floor had the date 1876 carved on it and, written in pencil, Henry Musgrave, 1892 [ but no Henry Musgrave recorded in Crakehall in the 1891 census, so it is unclear who he was ] .

In about 1974 Mr. Gilbertson bought the mill and converted it into a house, incorporating the wheel and some of the machinery as architectural features, but these were removed by a later owner.

Kirkbridge Mill

It is difficult to trace the history of the Kirkbridge area generally, and of the mill in particular, before the late 18th century. The problem is that although Kirkbridge lies within Crakehall township boundaries now, it seems to have been part of, or owned by, the manor of Langthorne. Although it is difficult to imagine any stream within the present boundaries of Langthorne supporting a water mill, there are regular records of a water corn mill there from medieval times. In 1246 Robert and Alan Lascelles bought five farms and a share in a messuage and a mill in Langthorne. This mill follows the ownership of the manor of Langthorne. The connection with Kirkbridge comes from the time that Kirkbridge mill was acquired by the Lister family, of Aiskew and later Coverham Abbey, in the 18th century. According to William Hird's diary, Anthony Lister, a dyer in Aiskew, inherited the estate of Thomas Raper, who had built Langthorne Hall in 1719 and was lord of the manor there. An abstract of Lister family deeds suggests that Lister acquired the property in 1737. Lister's property in turn passed to Edward Lister of Coverham Abbey and subsequent deeds show Anthony Lister owning the mill and farm at Kirkbridge. The idea that the Listers acquired the mill from Raper with the manor of Langthorne is supported by the architectural similarities between the mill house, with its mellow brickwork and stone door surrounds, and Langthorne Hall.

It is difficult to trace the history of the Kirkbridge area generally, and of the mill in particular, before the late 18th century. The problem is that although Kirkbridge lies within Crakehall township boundaries now, it seems to have been part of, or owned by, the manor of Langthorne. Although it is difficult to imagine any stream within the present boundaries of Langthorne supporting a water mill, there are regular records of a water corn mill there from medieval times. In 1246 Robert and Alan Lascelles bought five farms and a share in a messuage and a mill in Langthorne. This mill follows the ownership of the manor of Langthorne. The connection with Kirkbridge comes from the time that Kirkbridge mill was acquired by the Lister family, of Aiskew and later Coverham Abbey, in the 18th century. According to William Hird's diary, Anthony Lister, a dyer in Aiskew, inherited the estate of Thomas Raper, who had built Langthorne Hall in 1719 and was lord of the manor there. An abstract of Lister family deeds suggests that Lister acquired the property in 1737. Lister's property in turn passed to Edward Lister of Coverham Abbey and subsequent deeds show Anthony Lister owning the mill and farm at Kirkbridge. The idea that the Listers acquired the mill from Raper with the manor of Langthorne is supported by the architectural similarities between the mill house, with its mellow brickwork and stone door surrounds, and Langthorne Hall.In 1779 Edward Lister mortgaged the mill, when it was described as "a fulling mill with house adjoining, with stable, Christabel Close, Richardson Close, Batt, Lund, 5 acres". Three years later Lister sold the mill, which by that time also operated as a sawmill and oilseed crushing mill, to a Leeds woollen merchant, Edward Mirfield, together with 109 acres of land in one farm called Kirkbridge or South Farm. Mirfield built a new house (the farmhouse beyond the mill house) and established the orchard in front of the mill. The old mill house was used only as a warehouse. However, Mirfield had little time to enjoy his new estate, as he died three years later. The mill, now solely an oil mill for crushing linseed, was acquired by Richard Strangeways, gent., of Well, but the new house and farm were sold separately to William Hood of Yafforth (whose name is commemorated on the stone plaque from the old bridge). According to Hird's account, Strangeways bought several water mills in the area, with ambitious plans for developing the linseed oil industry as an adjunct to flax growing for linen manufacture. However, financial problems forced him to sell the mill at Kirkbridge to a family of linen weavers, the Walkers of Danby Wiske, together with a newly purchased field called Sandhill Close in which he was building the six workers cottages that still stand on the roadside just before the bridges. According to Hird the whole mill field was flooded as a mill dam at that time.

Mr. George Park, for many years owner of Kirkbridge Mill, told the story passed through generations of his family, of the activity of the mill at the height of the linen industry there. Flax was grown in large amounts on the surrounding farms and was spun and woven at Kirkbridge. Hemp was also processed there, and trade directories of 1830 and 1857 record the manufacture of ropes on the premises. Workers lived in the cottages on the road, in the mill outbuildings and in a dormitory for fifteen people in the top storey of the mill. This storey has since been removed, but an old photograph in the posession of Mrs Wilson (nee Sedgwick) who lived at High Mill farm in the 1970s, clearly shows traces of the old to storey window layout. Considerable alterations must have been made at the turn of the century - the daybook of the village joiner and undertaker, Luke Sedgwick, shows that he provided 12 new sash windows for Kirkbridge in 1891. The newspaper obituary of Mr. Sedgwick, who died in 1906 at the age of 84, records that he was born at Kirkbridge where his parents were weavers "of the old Crakehall linen, which was renowned for its durability".

In the 1970s, Mr Park said, there were French burr grinding stones still in the mill, and a gritstone dated 1764. He thought these were corn-grinding stones. A smooth black igneous stone there might have been used for oilseed pressing. The remains of a wooden waterwheel, with oak axle and wooden spokes, survived.

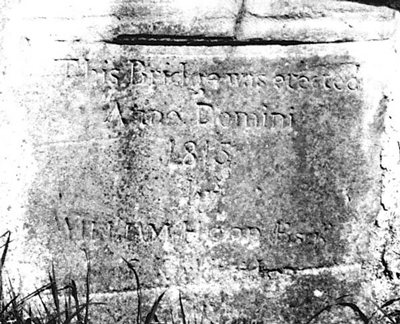

It must have been a severe blow to the village when, in about 1810, the mill was severely damaged by lightning. The Walkers were bankrupt in 1814, possibly as a result of this disaster and William Hood, who already owned the farm, bought the mill. Hood spent a lot of money improving the property. He built a stone bridge over the beck to replace a precarious ford and plank bridge across the mill dam. The bridge was rebuilt on a new alignment by the County Council in 1958, but the old stone plaque erected by William Hood can still be seen, now set into the adjoining wall.

This Bridge was erected

Anno Domini

1815

by

WILLIAM HOOD Esq.

Hood kept the mill running until he sold it and the farm to the Duke of Leeds at Hornby Castle, in 1825. By that time the linen industry was in decline in North Yorkshire and the mill reverted to a mixture of roles, as a corn mill, as a ropery and for grinding cattle feed. Benjamin Race, and afterwards his son Byers Race, were tenants there until the 1860s. John Boddy was tenant in 1871 and John Hobson in 1881 (John was also a partner of the Musgraves at Crakehall Mill at the time). The 1891 census records the mill as unoccupied - perhaps untenanted - and a William Dovenor was there in 1901. In 1919 the Park family took over the mill. They had been in the milling trade in the Scottish borders before moving to Yorkshire, first to Easby Mill, then to Aiskew Mill in the 1860s. They ground their own corn and that of neighbouring farms until the 1940s, after which the mill was used intermittently for the Park's farms. Up to 1955 it also generated electricity for the farm and worked a saw mill. It last turned its wheel in 1968.

3. The textile industry

The fulling and dying trade carried on by the Moses family at High Mill, and the linen weaving at Kirkbridge mill continued an involvement of Crakehall with the textile trade that dated back at least as far as the thirteenth century.Early in the Middle Ages the higher land around Leeming Beck and the Ure was highly valued for sheep rearing. Monasteries obtained grants of pasture for very large numbers of sheep - Jervaulx Abbey at Rookwith, Rievaulx Abbey at Bellerby, Easby Abbey at Tunstall and the Hospital of St. Leonard at Hornby. The Lords of Middleham had sheepcotes at Snape, Crakehall and Middleham, while the Conyers of Hornby had one at Appleton. The tythes of wool recorded in ecclesiastical tax returns of the period also show that sheep were a prominent feature of agriculture even in the arable farming areas of Richmondshire. It is not surprising that weaving became established as a cottage industry, and it seems that Crakehall became the regional centre for cloth finishing by 1300, with the construction of one of the first water-powered fulling mills in the country recorded in the extent of the manor made in 1298. The lay subsidy tax roll of 1301 records that the mill was operated by Hugh the Walker (ie. fuller) with his assistant Radulph the Fuller. The first fulling mill was almost certainly on the same site as the manorial corn mill - the present Crakehall Mill - the Manor Court Roll of 1450 records a complaint against the "putrid effusions" from the fulling mill and about the disrepair of the corn mill "in the same place". Hugh the Mercer was another prominent tradesman in the village. Several other estates soon built fulling mills as well. By 1327 the Scropes had them at Constable Burton and Masham, Jervaulx Abbey built one at East Witton and the Nevilles established additional ones at Thoralby, Aysgarth and Middleham.

The purpose of fulling was to felt and thicken the newly woven cloth. Originally it was trampled in troughs of water with fullers earth, which also removed some of the grease from the wool. A fulling mill replaced the walker's feet with wooden paddles worked by a cam driven by the mill wheel. The treated cloth was washed and then dried outdoors, stretched on wooden "tenters". The introduction of water-driven machinery must have increased efficiency enormously, as well as saving the fullers' feet.

The wool trade continued on a large scale well into the fifteenth century. Richmond was one of the principle markets, particularly for raw wool which was exported by Richmond merchants through the port of Newcastle to the low countries, and later to Calais as well. The Yorkshire abbeys, some of the biggest wool growers, exported their own wool to the low countries and Florence. Even Coverham, a relatively small and poor abbey, was contracted to sell 8 sacks of unsorted fleeces a year (almost 3000 pounds weight of wool) to a Florentine merchant, while Rievaulx and Jervaulx contracted for 50-60 sacks each. But while wool production continued at a high level during the agricultural depression of the early 15th century, cloth manufacture seems to have drifted away from the area. The accounts of the Ulnagers for the taxes they raised on pieces of cloth sold on the market show that in 1395 the Richmond-Bedale-Northallerton market was second only to Ripon-Boroughbridge in Yorkshire, but by 1470 it had declined into insignificance, losing its business to York which presumably provided a more convenient port and market. Richard of Bedale became one of the principle cloth merchants in York.

As the local market for cloth declined, so did the cloth finishing industry. By 1450 the manor court rolls record the "decayed and decrepit" state of the fulling mill at Crakehall. The Nevilles were reluctant to repair it because they could not find a tenant. By 1465 the Nevilles' fulling mills at Thoralby and Aysgarth were also unlet, and in 1507 the Middleham mill was untenanted too. The Crakehall fulling mill does not appear in any of the surveys of the manor during the 16th century, but it must have survived, for in 1608 commissioners examining ways of increasing revenue from the Crown estates included it on a list of mills that might be sold. However, cloth treatment seems to have gained a new lease of life in Crakehall at about this time. The Little Crakehall mill retained the name Walkmill and it seems likely that it was being used for treating and bleaching linen cloth. In the dales, linen had been woven for some time. John Leland reported that Grinton market sold "linyn cloth for the men of Swaledale" in the 16th century, and fields with names such as Hemp Croft and Line Garth were common around the lower dales. In Crakehall George Symondson had his Lineacre Close in 1600 and by 1610 the manor court was having to deal with serious pollution of the beck caused by people "ratinge hempe in the river". Repeated complaints appear in the court rolls - in 1616, for example, Widow Mason was fined 2d for "washing lyne in the stream" and Frances Jackson 4d for "ratinge lyne in the running river". These complaints relate to the first stage in making linen and hemp fibre, softening the flax stems in water and crushing them to extract the fibres. This was clearly woman's work! No fewer than ten women were fined in 1610 for the same misdemeanour. Perhaps the cottage industry was organised in some way. Probate inventories of the period show that some inhabitants of the village had substantial amounts of linen cloth stored in their houses. Isabel Clapham had 14 yards of linen cloth in her house in 1565, William Husband had 11 yards in 1589 and William Jackson had 10 shillings-worth of hemp and yarn in 1613. Weavers are recorded in the village throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries - the Ward and Mason families in particular - and it obviously continued as a significant cottage industry. Henry Mason's household goods in 1672 included "in the shope two lumes.. .one whele" and "in the parlor ...... sex pare of weaver geares and a shittle and other things belonginge to that trade". He had another spinning wheel in the barn.

It seems likely that the fulling mill kept working in some role throughout the 18th century. It was let for the considerable rent of £11 a year in 1730, and although its machinery was dilapidated when Johnson Moses, a fuller from Barnard Castle, leased it in 1765 its continuing use for cloth finishing of some kind is described in the lease: "the Bothams in which the mill and tenters are erected". As we have seen, Moses and his son established a thriving trade in cloth finishing there, with a large bleach yard. Linen weaving continued in the area, where the Allen brothers in Crakehall and George Brown in Hornby had sufficient business as weavers to take on parish apprentices in the early part of the nineteenth century. This local small-scale work could not compete with the steam-powered mills of the West Riding and Lancashire, particularly after the coming of the railway and improved roads. By the 1850s all mention of cloth manufacture has disappeared from accounts of the village.

4. Brewing and public houses

From the earliest times ale was the staple drink in rural areas, often as a safer alternative to polluted water. "Small beer" was still given to children in the 18th century and even ladies of fashion drank beer. No country seat was complete without its own brewhouse, and villages had common brewers, who often were also the local inn-keepers. There was a common brewhouse in Crakehall in 1367, and a later survey of the village suggests that this was attached to the common oven (bakehouse) that stood at the corner of the green above the bridge.Many farmhouses did their own brewing. Probate inventories from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century describe at least rudimentary brewing equipment in almost every house. Thus in 1608 we find in a farm house "one fatt [ie vat], 2 barrels, one wort seive, one wort tub" and in 1668 "In the Kitching - one furnace, one brewing vat, 6 skeeles, one brewing vessel". It was not only the farmers who brewed. In a joiners house were "in the cellar 2 hogsheads of beare" and "in the brewhouse one malt mill, two stools and other brewing vessels". The Crakehall area has always been good barley country and still produces barley for malting. Brewing ale for sale has been controlled by local government for centuries. Licenses for various aspects of the trade were granted by Justices of the Peace and the Quarter Sessions Court prosecuted those who traded without one. We find William Jackson being fined "for buying barley to make malt to sell without a license" in 1608, whilst in 1626 widow Anne Sickling was fined for "brewing ale without permission".

There have been brewers in both Little and Great Crakehall. The property now known as Malt Shovel House was the Malt Shovel Inn, owned by Camerons Brewery during the 20th century, until they sold it and it ceased to be a public house in the 1960s. However, it had a long history before that as a maltster's and brewer's. It was owned by the prosperous Lucas family of Little Crakehall in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was originally Henry Lucas's farmhouse and his probate inventory shows it consisting of a forehouse, a little room next to the forehouse, a high parlour, a low parlour, a kitchen and a milkhouse. As early as 1689 it had a malt kiln attached to it. By 1857 it was the Malt Shovel Inn, occupied by Martha Sadler, who was also described as a maltster in Kelly's Directory of that year. The 1871 census records a Mr. Lawson as the licensee, and in 1890 John Tindall was the innkeeper and also a butcher! There were extensive outbuildings behind the main house where brewing was conducted. An upstairs room, reached by an outside flight of steps, was used for dances and entertainment.

Another maltster operated in Great Crakehall, at the Black Horse Inn at the crossroads of the Newton le Willows road and the road to Cowling. Although this inn gained extra prominence due to the railway station nearby, it was there long before the railway and continued as a substantial business to the end of the nineteenth century. In 1871 Henry Dinsdale carried out malting there with his family and an assistant maltster who lived on the premises. Remains of the brick-built malting survive along the Newton road immediately west of the house.

The most important brewery was in Great Crakehall, where the Scott family had a substantial business in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The brewery was in buildings through the half-blocked arch in the cottage on the right hand side of the green soon after entering the village from the bridge. William Hird described it in his diary: "A common brewery was here, twas kept by Mr. Scott, Genteel he always did appear, His family held in note. Twas through an archway you did go, Nigh unto Allen's house [St. Edmunds House], And daughters he had only two, A carriage one did use" [he means an invalid carriage]. Scott also leased the maltkiln at the Malt Shovel about 1800.

The Bay Horse Inn is the only remaining pub in the village, but there have been several others within living memory. The Bay Horse dates from before 1719, when Marmaduke Richardson left it to his son, who farmed Mirefold. It probably became an inn in 1801 when Henry Plews, the brewer at Leeming Bar (later the Vale of Mowbray pie factory), bought it. In 1823 it was called The Reveller, after a famous racehorse owned by Mr Peirse of Bedale Hall. (Another of Mr Peirse's racehorses, Dr Syntax, gave its name to pubs all over the North of England). Camerons, the Hartlepool brewers, later took it over, renamed it the Bay Horse, and eventually sold it to the tenant, Mrs Gertrude Stelling, in the 1950s. At that time all the beer was still kept in barrels in the back beer cellar, where it was tapped off as needed, without even the aid of a hand pump.

The Malt Shovel, which has already been described, seems to have been the only pub in Little Crakehall, but a gentle stroll along the beck-side and over the bridge would soon have brought the thirsty traveller to the Crown Inn (now Brookside), which was a humble "beerhouse". Thomas Sadler bought Kit Collinson's blacksmith's shop on the site in 1806 and built the present house there. He used it for his shoe-making business while his wife sold "strong beer". Robert Moses was the licensee there in 1857, and in the 1860s John Pinkney was the landlord. Perhaps business was not so good by that time because John also advertisd himself as a sheep doctor. By 1890 it had become a butcher's shop. In the 1940s and 50s it was an unlicensed guest house.

For a short time a second beerhouse, the Railway Inn, was run by James Bates in the West End of Great Crakehall. Since the railway only reached Crakehall in 1855, and the premises were no longer a beerhouse in 1871, it must have had a short life. The Black Horse Inn was well established by the time the railway station was built, and was in a much better position to capitalise on the new source of customers.

5. Quarries and brickworks

Crakehall lies almost on the edge of the magnesian limestone belt that extends north to south along the centre of England. This yellow-grey stone is the typical building material of the area. Only a few miles to the west the limestone is the grey carboniferous limestone of the dales. The magnesian limestone outcrops at several places between Well and Catterick and was quarried on a considerable scale, both for building stone and for lime. In Crakehall, signs of quarrying can still be seen in the field immediately south of the beck opposite the Malt Shovel House, and further west, in Kilngarth Wood. There, the high rockface of the quarry is still exposed opposite High Mill Farm. This quarry, as its name implies, contained a limekiln, which is shown on a map of 1805 (click the thumbnail for maps of 1805 and 1913) and whose site can be recognised as an overgrown mound in the wood. Hird describes "vast carts" from Cleveland transporting lime from here in the 1790s, when Thomas Hodgson had the lime kilns. Hodgson was a "resolute and rash man" who seems to have had a knack of making enemies. When a horse belonging to his neighbour in Little Crakehall, Mr Joseph Moses, strayed into Hodgson's garth in his fury he killed it with an axe! Not surprisingly, he came to a sticky end. He retired to Theakston Grange where he was burgled, and later poisoned by Michael Simpson who had been another neighbour of his in Little Crakehall. Simpson was executed in York for his murder in 1798.

and whose site can be recognised as an overgrown mound in the wood. Hird describes "vast carts" from Cleveland transporting lime from here in the 1790s, when Thomas Hodgson had the lime kilns. Hodgson was a "resolute and rash man" who seems to have had a knack of making enemies. When a horse belonging to his neighbour in Little Crakehall, Mr Joseph Moses, strayed into Hodgson's garth in his fury he killed it with an axe! Not surprisingly, he came to a sticky end. He retired to Theakston Grange where he was burgled, and later poisoned by Michael Simpson who had been another neighbour of his in Little Crakehall. Simpson was executed in York for his murder in 1798.Stone from the small quarry on the opposite side of the beck facing the Malt Shovel was brought across the beck at the ford at the bottom of the lane that runs down the side of The Hermitage. Leases of the farm that is now High Barns alongside Kilngarth Wood included the right to excavate a certain length of the quarry face each year and the Theakston family operated it for several years.

Brickworks

There are very few brick houses in Crakehall, and no old ones except for the houses at Kirkbridge and brick decoration on a few houses on the green. The first brick-built house in the area was that behind the church in Bedale, built in 1710. Langthorne Hall, 1719, is another early one. But later, bricks were used for repairs, extensions and new chimneys. The earliest bricks were probably produced on the Beresford Peirse estate in Bedale, when they were burned on the building site. By 1750 bricks and, particularly, red roofing tiles were finding more general use, and the promotion of land drainage by the big landowners encouraged the manufacture of drainage tiles as well. There were at least three brick and tile works locally. A flourishing kiln operated in Aiskew by 1767 and a brick and tile works was established by the Duke of Leeds at Cobshaw, near Kirkbridge, before 1750. Both these works occupied sites close to clay deposits, and shallow remains of the claypits can still be seen. The third brickworks was at Rand Grange, where the remains of buildings and the flooded claypit still survive in Brick Kiln Wood, north of the railway. Later in the 19th century machine production of bricks on a huge scale put these local enterprises out of business.

6. Craftsmen and tradesmen

In an age of poor roads and transport, rural communities had to be much more self-reliant than nowadays, not only in the production of food but for all the other necessities of life - housing, furniture, clothing, tools and machinery. All villages had their complement of craftsmen able to supply these essentials, and even the coming of public stagecoaches and, later, the railways did not succeed in displacing them with products from the big towns. Only after the First World War did it become apparent that their days were numbered.Victorian directories and census returns still depict a fairly self-sufficient Crakehall. Both Great and Little Crakehall had tailors, dressmakers, masons, wheelwrights, shoemakers, joiners, blacksmiths and millwrights. A few have left a permanent record either in their surviving work or in local memory.

Matthew Ward, Builder and Joiner

Matthew Ward was the builder responsible for several of the 18th century houses we see in Crakehall today. Between 1743 and 1767 he built houses for John Remmer, William Castling, Mr. Plews and Mr. Musgrave, and there are records of him selling several other renovated properties. His work for Remmer was the fine pair of houses facing the beck on the old road to Little Crakehall, opposite the Malt Shovel - a splendid piece of building work with more fashionable style than most of the houses in the village. Ward lived in Little Crakehall and is recorded throughout his working life as a joiner or carpenter. He may, in fact, have operated as a property developer and building contractor. Several deeds for houses in the village record the sale by Ward of newly built or renovated houses. This kind of activity is familiar in villages today, not always with such pleasing results !

Mr Remmer's houses

The Hall Twins - The "Singing Blacksmiths"

The Hall brothers, Procter and Stephen, were born in Great Crakehall in 1813, the sons of the village blacksmith William Hall. After their apprenticeship they took over their father's business at the corner of the green on the right hand side as you leave for the bridge. Over the next 50 years they became notable figures in the district. In the 1870s Stephen had his own smithy in Little Crakehall by the bridge (at the bottom of "blacksmith's bank"). Procter continued to work as the smith in Great Crakehall until old age forced him into retirement with his daughter, in Marske in Cleveland. He died in 1892.

The twins owed their fame outside the village to their singing. As "singing blacksmiths" they were known as far away as County Durham, and one of Procter's granddaughters was told by an old man in South Durham how they used to finish their work in an evening by singing a hymn - "Glory to thee my God this night" - with their hammers beating time to the music. Another of their specialities was the Volga Boat Song.

You can see an article from the Dalesman magazine about them, here.

Luke Sedgwick - joiner and undertaker

In the late Victorian period a much respected figure of the village was Luke Sedgwick. His 'Day Book', a substantial leather-bound ledger, which reveals the enormous range of activities Mr. Sedgwick undertook, was retained by his grandaughter, Mrs. Catherine Wilson of High Mill Farm. Clearly the call must have been "send for Luke Sedgwick" whenever any little practical problem arose in the home or on the farm. His customers included the Duke of Leeds at Hornby Castle, Lady Cowell and Mrs Mitchell at the Hall, the Vicar, Captain Robson at Crakehall House, various farmers, the school, the cricket club - the list is endless.

The entries in his ledger (1873-1913) reflect life in the village one hundred years ago, when the Hall was fully staffed, the vicar was a wealthy man and farmers were the main employers of labour. Throughout his working life Mr. Sedgwick charged between 4s 6d and 5s for a full day's work (though sometimes he accepted payment in kind - eggs, butter, fowls and so on). He had a clear idea of the value of his working time. One entry for 1897 reads "Journey to the Vicarage for brace and bit not returned - 6d". Perhaps the vicar, Mr. Raven, had been trying a little 'DIY'; he was a keen amateur photographer and built a darkroom at the vicarage.

Although a joiner by trade, Mr. Sedgwick could turn his hand to other work with great facility. In his work for farmers we find him repairing and rebuilding gigs and carts, making new spokes for wheels, and repairing chairs and bedsteads. He charged 3d for repairing rakes and forks. He was the man to repair machinery as well - "axeld a grindstone, 1s; altering a whinnowing machine, 1s6d" and on a more domestic note, "new spring for American clock and fixing pointer on 8-day clock, 1s" at the Hall. It seems once a householder got him in, every little repair job was brought out - "looking glass repaired, 6d; umbrella repaired, 6d; painting flour tin, 3d".

However, his main work was domestic and farm joinery and carpentry. He replaced the roof timber of Low Mill in 1881, for £8-11-00, renovated Wassick Lodge at Langthorne for the Duke of Leeds for £4-5-0, and carried out numerous jobs at Crakehall House for Colonel Robson - fixing a pillar in the dining room, making a bridge acrosss the beck, fixing trellis work on the front of the house. Interestingly, in 1887, we find him "attending to a water closet" there. We also read of him "setting out work on water closet and making the same" at the Hall in 1876, and "panneling a room at the Vicarage".

At the Hall and the Vicarage he regularly, over a period of more than 20 years put up the sunblinds each May and removed them again each October (in 1891 they stayed up until Novemer 21st - an Indian Summer?). Perhaps the work for the Hall reflects best the versatility of Luke Sedgwick and shows the respect people had for his reliability over so many years. Here is a selection of entries concerning his work there:

22nd June, 1876 - Setting out work on water closet and making the same. 7 days.

12th February, 1877 - Removing floor and wainscoating in search for dead rats. 4 days.

3rd March, 1877 - Setting 5 razors

28th August, 1877 - Getting ice box into the cellar.

29th August, 1877 - Taking the bees to the moor (removed 28.9.77)

19th August, 1878 - Piano packed.

14th July, 1879 - Repaired Mrs. Mitchell's parasol.

!!th August, 1880 - Jaunting car repaired.

5th May, 1882 - New handle for lawnmower.

12th May, 1882 - Covered new couch.

15th July, 1882 - Net stakes for lawn tennis.

31st July, 1883 - Key liberated.

20th June, 1887 - Preparing for, and fixing flag [he did the same at the vicarage - it was Queen Victoria's golden jubilee).

6th September, 1890 - Erecting aviary.

30th August, 1894 - Covered seat of W.C.

30th September, 1896 - Altering aviary.

Mr Sedgwick was also an undertaker, and dealt with at least 90 funerals between 1873 and 1903. There is an amusing story about his undertaking work in the article about the Hall twins here.

It is not surprising that Sedgwick was a successful man - an intelligent craftsman of boundless energy and prepared to make a penny anywhere. Whether you wanted a case for stuffed birds (£1-5-0) or a greenhouse (£15-11-6) he was your man. He did not forget that he was a craftsman though. He spent 18 days, at a total cost of £9-5-0, repairing an antique bed for the Dodsworths of Thornton Watlass Hall in 1875.12th February, 1877 - Removing floor and wainscoating in search for dead rats. 4 days.

3rd March, 1877 - Setting 5 razors

28th August, 1877 - Getting ice box into the cellar.

29th August, 1877 - Taking the bees to the moor (removed 28.9.77)

19th August, 1878 - Piano packed.

14th July, 1879 - Repaired Mrs. Mitchell's parasol.

!!th August, 1880 - Jaunting car repaired.

5th May, 1882 - New handle for lawnmower.

12th May, 1882 - Covered new couch.

15th July, 1882 - Net stakes for lawn tennis.

31st July, 1883 - Key liberated.

20th June, 1887 - Preparing for, and fixing flag [he did the same at the vicarage - it was Queen Victoria's golden jubilee).

6th September, 1890 - Erecting aviary.

30th August, 1894 - Covered seat of W.C.

30th September, 1896 - Altering aviary.

There is a web site devoted to members of the Sedgwick family all over the world, here. Dressmaking - Miss Sedgwick

The ledger in which Luke Sedgwick recorded his work had originally belonged to his sister, who died at the age of 36 in 1864. She was working as a dressmaker until the year before her death and had used the ledger for her accounts. She toured the local farms, doing general sewing work at 1s a day (presumably with a meal) , and also did larger dressmaking and tailoring commissions. For Mrs. Wright, of Manor House Farm, for example, she records during 1856-57 making 5 dresses, 2 shirts, a pair of sheets, a pair of trousers, a pair of stays and four "shimees". Agricultural equipment - Mr Sherwood

Some of the outbuildings at Kirkbridge Mill were used at the end of the last century by a Mr. Sherwood to manufacture his patent design of agricultural machinery. Mr. Parks showed a Canadian airman round the farm late in World War II, who recognised an old piece of machinery labelled 'Sherwood - Maker' as identical with a machine on his own farm in Canada. The Sherwoods manufactured machinery there throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, describing themselves as 'Farmers and Reaping Machine Manufacturers'. The large family also ran a farm of 165 acres.

7. Shops

For centuries general trade centred on Bedale market, and it was there that retail shops grew up during the 18th and 19th centuries. "All roads led to Bedale" in medieval times and on Tuesdays people must have thronged the road from Crakehall, possibly stopping at the White Cross at the junction with the bridle track from Langthorne, to hear the cannons from Coverham and Easby Abbeys preaching. Until the establishment of the fortnightly cattle market in 1837, the highlights of the year were the cattle fairs on Easter Tuesday and Whit Tuesday, and the two-day July and October fairs. Even in Victorian times carriers operated their carts from all the Bedale public houses on market days, each serving a separate village. In 1857 Pattinson's cart left the Oddfellows Arms for deliveries to Crakehall. In the villages, shops were far from the modern idea of a village general store, though they did share some of the unexpected juxtapositions of goods and services. In Crakehall, John Remmer advertised himself as a 'grocer and draper' in 1823, while in 1857 Anthony Miller was a 'shopkeeper and wheelright'. In 1891 Crakehall had a grocer and Black & White Tinsmith (Robinson Morton), a grocer and sheepdoctor (John Pinkney) and a butcher and victualler (John Tindall at the Malt Shovel).Mrs. Stelling, born in 1885, recalled that when she was a girl in the village you went to one house for paraffin, to another for yeast, to a third for butter, and so on - everyone seemed to sell a bit of something. There was certainly a growth in retail trade in the village in the second half of the nineteenth century. The 1851 census shows two grocers, a tallow chandler, and a butcher. By 1857 Great Crakehall had a grocer and butcher (Thomas Cannon, near the Bay Horse Inn), a greengrocer (Jonathon Jackson), a grocer and draper (Henry Stephenson), while Little Crakehall was served by John Barron, a coal dealer, George Harland, a greengrocer, John Patterson, a butcher, and Stephen Braithwaite, another butcher. The 1871 census, taken when the population was at its highest, mentions no fewer than 5 grocers, 2 butchers, a greengrocer, a butter dealer and even a 'dealer in pots'. After the First World War the number of village shops declined as the population fell, and in the 1930s Crakehall finally lost its butcher and its greengrocer. By that time there were just two general shops, both in Great Crakehall - Mrs Pinkney's at the end of the terrace next to Village Farm and Mr King's, in the house now called St. Edmonds House. Mr. King was also a yeast dealer and he would never have thought of selling the pennyworth of red apples that were such an attraction at Mrs. Pinkney's. By this time Mrs. Nicholson had a Post Office in the village, on the south side of the green, and she confined her trade to stamps, postcards of the village, and newspapers. In her shop trade was conducted with great solemnity and ceremony in the gloom of the small-windowed cottage.

Travelling shops were also a feature of village life, and in this century there have been visiting butchers, fishmongers, fish and chip purveyors and tailors representatives. Mr. Kit Simpson of Crakehall began work for Hewsons, the Bedale clothiers, in 1919 and for almost 50 years he did the rounds of the local villages taking measurements and orders for mens' and womens' clothes. These were made up by 'cut, make and trim' people in Leeds, then returned to Hewsons for delivery. This kind of business gave way in time to the Mail Order Catalogue.